- Zoboli Patrizia

- Review

A Painful Shoulder – Case Report of Necrotizing Fasciitis

- 3/2019-Ottobre

- ISSN 2532-1285

- https://doi.org/10.23832/ITJEM.2019.032

Zoboli Patrizia1, Maldina Laura1,Grulli Francesca2, Montanari Simone1, Alboni Sergio1, Ferrari Anna Maria3

- Emergency Physician in Hospital Magati USL Scandiano (Reggio Emilia)

- Medical doctor under training in Emergency Department in Pavia University

- Medical Director DEU Azienda Unitaria Sanitaria Locale di Reggio Emilia-IRCCS Istituto in Tecnologia Avanzata e modelli assistenziali in oncologia

Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a rare but rapidly evolving disease which can also determine the exitus of the patient. Almost all the patients with NF access to the Emergency Department, and it is a great responsibility of the emergency physician to make the right diagnosis as soon as possible. For this reason it is always important as an emergency physician to be alert for this rare pathology, because rapidly evolving and possibly lethal. Only with an early diagnosis and treatment can we positively influence the prognosis “quad vitam” and “quoad valetudinem”. We report the case of a 42 years-old woman with a silent medical history, presented to the emergency department of the peripheral hospital of Scandiano (RE). She showed up with an atraumatic pain in her right shoulder. The clinical examination was suggestive for a case of cervicobrachial neuralgia, although two days before the beginning of the shoulder pain the patient had a self-limiting feverish episode. 24 hours later the shoulder pain was becoming very intense and irradiated also the lumbar region, but the patient was afebrile and the worsening of the symptoms was not related to the clinic examination. After only two hours the patient began to deteriorate rapidly, presenting a septic shock with hypotension, increased levels of acute phase reactants of inflammation and initial signs of Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome, (MODS).

The Emergency Physician of the peripheral hospital noticed the rapid evolution of the situation and centralized the patient in the HUB Hospital of Reggio Emilia, where a CT scan allowed the early diagnosis of the necrotizing fasciitis. The patient was treated with empirical antibiotic therapy, optimized after the results of peripheral vein blood cultures and the microbiological tissue analysis obtained from the surgical debridement. The early onset of antibiotics, surgery and good post-surgery wound care were the cornerstone in the recovery of the patient.

Keywords

Necrotizing Fasciitis (NF); ultrasound (US) of soft tissues; Emergency Department (ED); Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome, (MODS); Emergency Physician (EP), Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Introduction

Necrotizing fasciitis is an acute and rapidly evolving infection that primarily involves the Fascia of muscles, with possible wide extension in the surrounding soft tissues through the venous and lymphatic vessels, followed by thrombosis and gangrene. If not diagnosed and treated quickly, it evolves into septic shock, with systemic toxicity and multi-organ failure1-2.

The types of soft-tissue necrotizing infection can be divided into four classes according to the types of bacteria infecting the soft tissue. The type 1 infection (70-80% of cases) is polymicrobial and generally it involves perineum (Fournier syndrome) or the back. Patients with many co-morbidities or immunosoppression are often involved.

Type II infection (20-30%) is monomicrobial due to group A Streptococcus beta-hemolytic (GAS). This mainly concerns young people without co-morbidity but with a history of trauma, surgery or drug abuse.

The type III infection (<1%) is monomicrobial and involves Gram + or Gram – such as Vibrio, Clostridia, Eikenella, Aeromonas. This infection is contracted through a continuous solution of the skin or by ingestion of crustaceans contaminated by pathogens2-3.

Some authors have described the type IV infection as fungal etiology (Paz Maya, S; Dualde Beltrán, D; Lemercier, P; Leiva-Salinas, C (May 2014). “Necrotizing fasciitis: an urgent diagnosis”. Skeletal Radiology. 43 (5): 577–89.)

The prognosis “quoad vitam” and “quoad valetudinem” varies from 20 to 80% and depends on the early diagnosis and the body area involved. In fact there is a better prognosis if the necrotizing fasciitis involves a limb, because amputation is possible, while there is a worse prognosis if there is involvement of the back, the neck or the perineum.

This disease is often under-diagnosed, due the underhanded and non-specific clinical presentation and rarity of this disease, although its incidence is increasing in recent years.

The reasons why the incidence of the necrotizing fasciitis is increasing can be attributed to several reasons: firstly changes in aetiological agents and reduced sensitivity to antimicrobial agents; then the increased transplant surgery with consensual increase of immunosuppressive therapy.

The third reason is the increase in the number of patients suffering from cancer (using chemotherapy treatments, including biological drugs), diabetes, drug addiction, chronic vascular diseases, trauma. Emergency Departments play a crucial role in diagnosing NF4, for specific and early investigations and for urgent treatment, both medical (antibiotic ad fluid therapy) and surgical (debridement).

Sometimes patients affected by these rare diseases first refer to a peripheral hospital, so the Emergency Physician needs to know this pathology to raise the suspicion of NF, based on clinical presentation and the patient risk factors (eg. using the LRINEC score – Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis score).

Once this pathology has been hypothesised, it should be confirmed by first-level investigations (eg: ultrasound examination of soft tissues) and if the diagnosis is confirmed patients may need to be directed to a “hub” center, to perform a CT scan or a MRI, to be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team (infectivologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist), for a safe diagnosis and treatment. The time factor is crucial for NF prognosis, both in terms of mortality and morbidity.

In summary there is a triad of factors that make the correct diagnosis difficult: First the rarity of this pathology, although its incidence is increasing, so sometimes the Emergency Physician doesn’t have a great experience of this pathology. Second the non-specificity of the initial symptomatology

Thirdly the severity of the prognosis of this pathology if not early recognized.

Case Report

We report the case of a 42 years-old woman who presented to the emergency department of the peripheral hospital of Scandiano (RE) on March 2, 2019 for an atraumatic pain in her right shoulder. She has a silent medical history and no history of drug use.

She reports waking up in the morning with worsening shoulder pain associated with functional impotence. The patient also reports a low-grade fever 2 days earlier, without cough or dysuria, spontaneously resolved.

At the first clinical evaluation of the patient in the ER she was apyretic, complaining only about the pain in the shoulder, without cutaneous rush or deficiency of the peripheral nerves.

She strongly denies recent trauma. The orthopedic specialist evaluated the woman and diagnosed a cervicobrachial neuralgia. After the administration of 1g of paracetamol the pain disappears and the patient has been discharged with the suggestion of taking NSAIDs. After 24 hours, patients return to the ER of Scandiano, complaining again pain in the right shoulder with pain irradiation also in the right lumbar region. She was still apyretic.

The clinical examination highlighted an important muscular contraction of the shoulder (“as hard as marble”), associated with whitish color of the shoulder skin and a small area of violaceous color at the axillary level.

The patient was treated with intravenous analgesic and biohumoral tests were performed. Pending the results of the exams, we detected hypotension (PA 80/60), treated with a liquid infusion.

An ultrasound was performed, which reasonably excluded aortic dissection (no pericardial effusion, normal aortic box, no dilation of the abdominal aorta, no pleural or endoabdominal effusions).

The blood gas analysis showed the presence of metabolic acidosis with high lactates.

Finally the blood tests showed: Leucocytes 3.66 x1000; Hb 9 g / dl, PLT 197 x1000, Glucose 105 mg/dl. Na 133 mmol / lt. Creatinine 2.44 mg/dL, C-reactive protein 29 mg / dL (normal range 8 – 30 mg/dL), procalcitonin 14.5 ng / ml.

If we apply the LRINEC score3-4 to this patient the result is 10 points: high risk.

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) | mg/L | score points |

| <15 | 0 | |

| >15 | 4 | |

| White blood cell count | per mm3 | |

| <15 | 0 | |

| 15-25 | 1 | |

| >25 | 2 | |

| Hemoglobin | (g/dl) | |

| <13.5 | 0 | |

| 11-13.5 | 1 | |

| <11 | 2 | |

| Serum Sodium | mmol/L | |

| >135 | 0 | |

| <135 | 2 | |

| Serum Creatinine | mg/dl | |

| <1.6 | 0 | |

| >1.6 | 2 | |

| Serum Glucose | mg/dl | |

| <180 | 0 | |

| >180 | 2 |

Table 1. LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score applied to the clinical case of thos report

According to the LRINEC score: <5 points is a low probability of NF; 6-7 points is an intermediate risk, > 8 points suggest an high risk of NF. A CT scan and advice from the infectious disease specialist are not available at the peripheral hospital at night and at weekends. For this reason our patient has been centralized in the Hub center of Reggio Emilia, where she has performed blood cultures and a CT of the neck and thorax, that identified inflammatory imbibition of the laterocervical soft tissues of the right hemithorax and mediastinal adipose tissue.

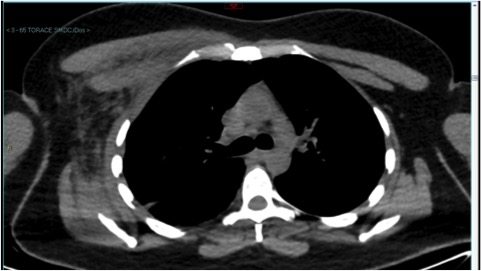

(Figure 1)

Figure 1. Thorax CT scan, showing the inflammatory imbibition of the right laterocervical soft tissues and of the right hemithorax and mediastinal adipose tissue

Despite the rapid volume filling, after few hours the patient was still hypotensive and it was necessary to give her an infusion of noradrenaline.

She also started antibiotic therapy with daptomycin + meropenem + clindamycin and was admitted to the operating room for soft tissue debridement surgery. Blood cultures and microbiological analysis of intraoperative tissue samples were all positive for streptococcus beta-haemolytic group A piogenes group A beta-hemolytic associated with toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST).

After 3 days a new incision was necessary for debridement surgery and positioning of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT).

On the fifth day she performed a lower limb compression ultrasound (CUS) that evidenced a thrombosis of the sural vessels in the middle III of the right calf, and a therapy with LMWH (Low molecular weight heparin) was initiated. One month later the patient was discharged in excellent condition, after a brief cycle of physical rehabilitation (due to protracted bedding).

In conclusion we assume that axillary hair removal is likely to be the cause of this infection.

Discussion

From this clinical case we can make several considerations. First of all the difficulty of making the diagnosis of NF, especially in a peripheral hospital, where sometimes the CT scan or the advice of the specialist in infectious diseases are not available.

For this reason we need to improve the scientific expertise of the emergency physician in the suspicion of NF, based on the history (predisposing factors such as immunodepression, trauma, comorbidities, etc.) and clinical examination (the pain in the site involved is disproportionately intense in relation to the clinic, inspection of the skin that appears first whitish, swollen and shiny, then bluish and with ecchymotic areas).

In conclusion, as emergency physician, we need to raise the suspicion of an NF in all situations that can simulate or coexist with it (e.g. erysipela, cellulitis, diabetic foot, skin abscesses) and which show disproportionately intense pain in relation to the clinic and the physical examination.

Ultrasound can be helpful in this situation for differential diagnosis.

Learn and use the ultrasound in the Emergency Department5,6,7,8,9 is very important for many reasons: it highlights possible outbreaks of infection and for differential diagnosis in case of fever, highlight a venous blood vessel thrombosis, evaluate and control the diameter and collapse index of the VCI (e.g. for septic shock), in case of infection of soft tissues, shows the presence of abscesses, pyomyositis, cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.

Suspicious factors of NF ultrasound are the lack of normal regular fibrillar architecture of muscle with increased hyperecogenicity, irregular “lumps”, presence of fluid collection (> 4 mm) near the deep band, a hyper-ecogenic band thicker than 4 mm.

In addiction the presence of gas inside the muscle is easily detected as a “comet tail” artifact with ultrasonography and as a crackling sound at the tissue pressure during the clinical examination5,6,7,8,9. In case of high clinical and instrumental suspect of NF, biohumoral tests (blood counts, CRP, PCT, CPK, LDH, electrolytes, transaminases), venous blood gas analysis for the research on lactates should be performed and the LRINEC score applied.

Where available, a TAC of the area concerned shall be required.

If the clinical suspicion of NF is high, it is necessary not to waste time and centralize the patient in a first level center for a multidisciplinary evaluation (infectious pathologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist) to protect the patient’s survival.

Conclusions

The necrotizing fascitis, although still a rare disease, usually has as first access the emergency department.

The aspecific symptomatology of this pathology requires the maximum alert of the physician, who must use all available tools to make the right diagnosis: past history, physical examination, use of the appropriate score, biohumoral tests, soft tissue ultrasound.

These basic surveys can be carried out in all hospitals, even if they are peripheral.

But if NF suspicion remains high, it is important to centralize the patient as quickly as possible, perform a CT scan, multidisciplinary evaluation and possible surgical treatment.

The emergency physician is responsible for the fate of these patients, whose prognosis is time-dependent.

Bibliography

- P Di Gregorio, A Aliffi, M Bollo, Salvatore Galvagna “Fascite necrotizzante: descrizione di casi clinici e rassegna della letteratura”. Le Infezioni in Medicina n.3, 177-186,1999

- Esposito, S Leone, S Noviello, F Ianniello “Analisi delle linee guida esistenti per il trattamento delle infezioni della cute e dei tessuti molli”. Le infezioni in Medicina Suppl 4, 58-63,2009

- A Venturi, D Rizzoli, M Cavazza “La fascite necrotizzante: approccio clinico e diagnosi nel DEA”. Emergency care journal Anno IV numero 1 febbraio 2008 pg 15-19.

- F Tosato “La Fascite necrotizzante: un’ardua sfida per i medici di urgenza” Commento al Caso. Emergency care journal Anno IV numero 1 febbraio 2008 pg 19-21.

- M reza Hayeri, P Ziai, M Shehata et al. “Soft –Tissue Infection and Their Imaging Mimics: from Cellulitis to Necrotizing Fasciitis” RadioGraphics 2016; 36:1888-1910

- L.F Chau, J.F.Griffith “Musculoskeletal infections: ultrasound appearances” Clinical Radiology (2005) 60, 149-159

- Zui-Shen Yen, Hsiu-Po Wang, Shyr-Chyr Che net al “Ultrasonographic Screening of Clinically-suspected Necrotizing Fasciitis” Academic Emergency Medicine 2002, 9:1448-1451

- W Shyy, R Knight, R Goldstein et al “Sonographic Findings in Necrotizing Fasciitis” J Ultrasound Med 2016; 35:2273-2277

- A Testa, R Giannuzzi, V de Biasio “Case report:role of bedside ultrasonography in early diagnosis of myonecrosis rapidly developed in deep soft tissue infections” J ultrasound 2016 Sep; 19 (3):217-221.