- M. C. Cedrone

- Original Article

Emergency Department as an epidemiological observatory of Human Mobility: the experience of the Moroccan population

- 2/2018-Luglio

- ISSN 2532-1285

- https://doi.org/10.23832/ITJEM.2018.018

* Emergency Department Policlinic Umberto 1°,

Sapienza – University of Rome, Italy

Abstract

Introduction

The problem of migratory flow of people is very ancient, and processes due to globalization and/or political issues led to new kind of human mobility.

This contributes to shift social and economic inequalities, within the countries that host migrants, increasing the burdens deriving from their needs.

We can consider Emergency Departments (EDs) as privileged observers of population health needs which reside or pass in a given area: people who cannot access to other facilities address to ED because it is the only Healthcare Facility avaiable 24-hours a day, including holidays, either for administrative issues, because ED takes care of all patients who access, even if not enrolled in the National Health Service. These characteristics are particularly related to the migrant population, people often in need and without alternatives.

ED thus becomes the only traceability tool for people who otherwise would not leave any sign, having actually no economic resources, residence or even identity card. This is true also from a chronological point of view, since we can observe the variation over time of Health needs of a given population.

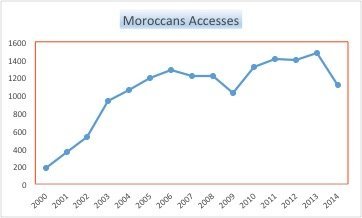

To this aim, we conducted a retrospective study of the accesses to Rome metropolitan area EDs, from January 2000 to December 2014. After having generally studied the North African population facing the Mediterranean basin (ITJEM n.1/18), we are going now to document specific data about Morocco population and their peculiarities.

Demographic and health characteristics of Moroccans in Italy and in Rome

The Moroccan community appears since the 70’s, among the main protagonists of the migration phenomenon in Italy, also due to the geographical proximity of the countries.

Migration numbers have constantly grown up, leading the Morrocans to stand among the first three populations of immigrants residing. [1]

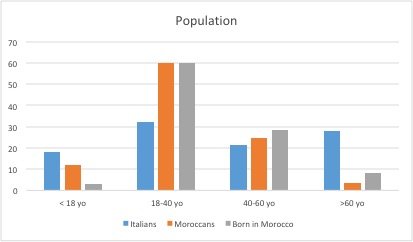

The latest ISTAT data, relating to Moroccan migrants present in the Italian territory until the 1st January 2015, reported 518,357 people (55.4% men and 44.6% women), equal to 13.2% of all non-EU citizens. The main reason to explain these numbers could be the “reunification with the family” (66% of total), instead the number of new entrants seems decreasing.

Furthermore, the number of Moroccans who have acquired Italian citizenship increased (29,025 in 2014, +14% compared to the previous year). This has a substitute effect: the number of non-EU citizens decreases in favor of “new” Italian citizens of foreign origin.

In 2015, the average age was 30 yo. Altogether almost half of Moroccan citizens was <30 yo (46% of total), while 14% was >50 yo. 71.7% of Moroccans live in the northern regions, 13.95% in the southern ones and 14.3% in the central Italy.

In Lazio reside at least 3% of Moroccans, the largest part of which in Rome and itsprovince: on 1st January 2015 the numbers were 13,336 people, with a growth of +4.1% compared to the 2014. 62.6% of these live in Rome. [2.3.4.5.6]

The diseases that affect the Moroccan community in Europe, according to the scientific literature, are those ones related to cardio and cerebrovascular systems. Related risk factors are hypertension [7,8], obesity [9,10,11], diabetes [12,13,14]; the same widespread in both the countries, origin and residence.

Aim of the study

This study assesses the health status of a Mediterranean basin population next to Italy, quite numerous because of its migratory flow, in order to record any peculiarities and possible changes in health status over the years, compared to Italian ones.

This population was chosen because of the above characteristics and the relative stable residency and inclusion in our social context.

Emergency Department was also chosen as an observatory tool, even if very unusual for such studies.

Materials and methods

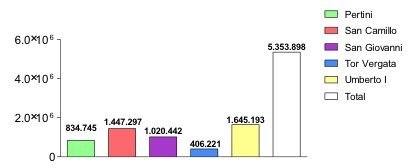

We conducted a retrospective study on patients who referred to the Emergency Department of five hospitals in the Rome metropolitan area: Policlinic Umberto I, Policlinic Tor Vergata, San Camillo Forlanini Hospital, San Giovanni Addolorata Hospital, Sandro Pertini Hospital.

We examined the ED accesses from January 2000 to December 2014. Each access is registered by the GIPSE computer system (which records the activities in ED and collects data requested from Lazio Region) in which patient information is entered, together with the reason of admission, the relative priority code and the clinical outcome: discharge, hospitalization, transfer to another hospital or death.

Furthermore, it collects useful information about health status of the population.

We extrapolated patients from Morocco from approximately 5,000,000 accesses recorded during the 14 years of the study, noting age, gender, reason access and final diagnosis identified according to the international classification of diseases (ICD-9 CM: International Classification of Diseases-9th revision-Clinical Modification).

We compared the prevalence of this information with the one of the Italians, the majority of the citizens who, during the period of the study, came to the Emergency Department of the five Roman hospitals. Some data relating to the natives of Morocco were compared with those relating to other populations in North Africa.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Chi-square Test to compare the different citizenships total infections and respiratory infections with their relative hospitalization. All tests were performed in two study-arms. Poisson regression models were constructed to identify variables independently associated.

The variable “Citizenship” (0 = Italian citizens, 1 = Moroccan citizens, 2 = Italian citizens born in Morocco) was treated as a “dummy” variable, using Italian citizenship as a reference (0).

The following variables have also been added: “gender” (0 = female; 1 = male); “age” (continuous v.); “2000-2014 time interval” (continuous v.), “triage code assigned to access“ (categorical v.) and “outcome” (categorical v.). A value of p less than 0.05 was considered significant.

The tests were performed using the Stata 15 software (Statacorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive College Station, Texas 7784 USA).

Results

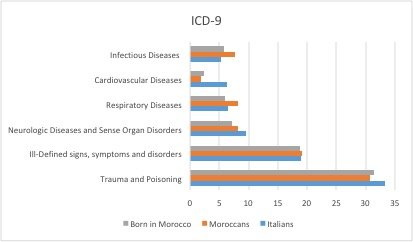

Diagnoses related to other ICD-9 categories do not find particular differences from those related to the Italian population (Figure 4).

Figure 1

Infectious diseases

|

Italians N° (%) |

Moroccans N° (%) |

Moroccans with Italian citizenship N° (%) |

Pv |

|

|

|

||||

|

Infectious Diseases |

243.568 (5.35) |

1.211 (7.72) |

– |

0.000 |

|

– |

1.211 (7.72) |

133 (5.82) |

0.001 |

|

|

243.568 (5.35) |

– |

133 (5.82) |

0.313 |

|

|

Hospital Admissions |

55.578 (22.82) |

207 (17.09) |

– |

0.000 |

|

– |

207 (17.09) |

26 (19.55) |

0.478 |

|

|

55.578 (22.82) |

– |

26 (19.55) |

0.369 |

|

|

Respiratory Infectious Diseases |

186.865 (4.10) |

913 (5.82) |

– |

0.000 |

|

– |

913 (5.82) |

79 (3.46) |

0.000 |

|

|

186.865 (4.10) |

– |

79 (3.46) |

0.121 |

|

|

Hospital Admissions |

43.894 (23.49) |

155 (16.98) |

. |

0.000 |

|

– |

155 (16.98) |

10 (12.66) |

0.3231 |

|

|

43.894 (23.49) |

– |

10 (12.66) |

0.023 |

Respiratory infectious diseases

Moreover, the risk is higher in the male gender (IRR 1.08; CI 95%: 1.07-1.09, p <0.001), while it decreases with increasing age (IRR: 0.96; CI 95%: 0.96-0.96, p <0.001).

Cardiovascular diseases

The diagnoses of Cardiovascular Diseases were 6.3% for Italians, 1.8% for Moroccans and 2.4% for Moroccans with Italian citizenship (Figure 4).

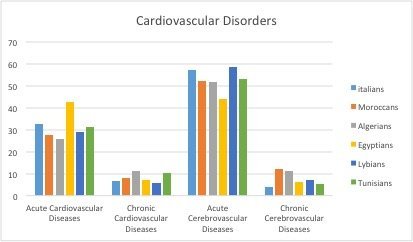

Within this ICD-9 category, Italians and Moroccans have been compared with the populations of North Africa (i.e. Algerians, Egyptians, Libyans and Tunisians), which shared geographical proximity and young age, and four diagnostic groups were found: acute and chronic cardiovascular diseases and acute and chronic cerebrovascular diseases. In particular, acute cerebrovascular diseases had a higher rate of diagnosis for all six populations (57.8%), followed by acute (31.4%) and chronic cardiovascular diseases (8.2%) and finally by chronic cerebrovascular diseases (7.6%). Italians had a higher rate of diagnosis of acute cardiovascular diseases (32.4%) than almost all other populations examined (Algerians 25.9% vs Egyptians 42.7% vs Libyans 28.8% vs Moroccans 27.4% vs Tunisians 31.4%).

The same was true for acute cerebrovascular diseases with 57.2% for Italians, 51.8% for Algerians, 44% for Egyptians, 58.6% for Libyans, 52% for Moroccans and 52.9% for the Tunisians. As for chronic diseases, Italians had a lower percentage of diagnosis compared to almost all other populations, both in relation to cardiovascular diseases (Italians 6.6% vs Algerians 11.4% vs Egyptians 7.3% vs Libyans 5.6% vs Moroccans 8.2% vs Tunisian 10.5%) and cerebrovascular diseases (Italians 3.8% vs Algerians 11.1% vs Egyptians 6% vs Libyans 7% vs Moroccans 12.3% vs Tunisians 5.2%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Discussion and conclusion

The Moroccan population differs from the Italian one for a larger number of diagnoses belonging to ICD-9 codes “Infectious Diseases” and the subgroup “Respiratory Infectious Diseases” mostly.

But considering admissions, we see that Italians are more frequently admitted on the other hand. This could be explained because of a more vulnerability of Italian population to complications, because is older than the Moroccan one, and even because of the improper use of the ED by the host population, usually not enrolled in the National Health Service, and so more frequently and improperly addressed hospitals rather than to general practitioner or other medical services, for diseases that do not require emergency treatment at all. [31]