- Silvia Iorio

- Original Article

Emergency Department as an epidemiological observatory of Human Mobility: Rome Metropolitan Area (EMAHM).

- 1/2018-Febbraio

- ISSN 2532-1285

- https://doi.org/10.23832/ITJEM.2018.007

Silvia Iorio*, Giuseppe Migliara**, Carolina di Paolo**, Annamaria Mele**, Grazia Pia Prencipe**, Lorenzo Paglione**, Livia Maria Salvatori**, Corrado De Vito** and the EMAHM Group: Baldini E., Bertazzoni G., Cipollone L., Gazzaniga V., Grasso F., Guglielmelli E., Londei A., Massetti P., Montanari A., Pugliese F.R., Ricciuto G.M., Ruggieri M.P., Suppa M., Susi B., Villari P.

Abstract

This study focuses on the analysis of Big Data obtained from the Emergency Departments (EDs) of five hospitals located in the metropolitan area of Rome, Italy. The analysis of ICD9-CM discharge diagnoses shows clear differences between the Italian population and the North African population and confirms that many of the dynamics and health conditions regarding migrants are due to the inappropriate use of health services and, eventually, of the EDs. Our results afford indication about how we could identify shortcomings and critical issues within the primary care system and, more generally, in the management of psycho-social and socio-economic support for immigrant populations.

Introduction

Methods

Data on EDs accesses from 1999 to 2014 in Umberto I University Hospital, San Giovanni Hospital, San Camillo Hospital, Tor Vergata University Hospital and Pertini Hospital were retrieved from the information system “Gestione Informazione Pronto Soccorso Emergenza” (GIPSE), that records the information on patient charts and the entire route within the Emergency Department (ED), from triage to discharge. Through the nationality variable, the accesses were grouped into: Italians, Algerians, Egyptians, Libyans, Moroccans and Tunisians. The descriptive statistics of accesses for year, gender, age, and main diagnostic category by ICD9-CM, triage, and outcomes were calculated for each population. Statistical analysis were performed using Stata 15.1 (Statacorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, Texas 77845 USA).

Results

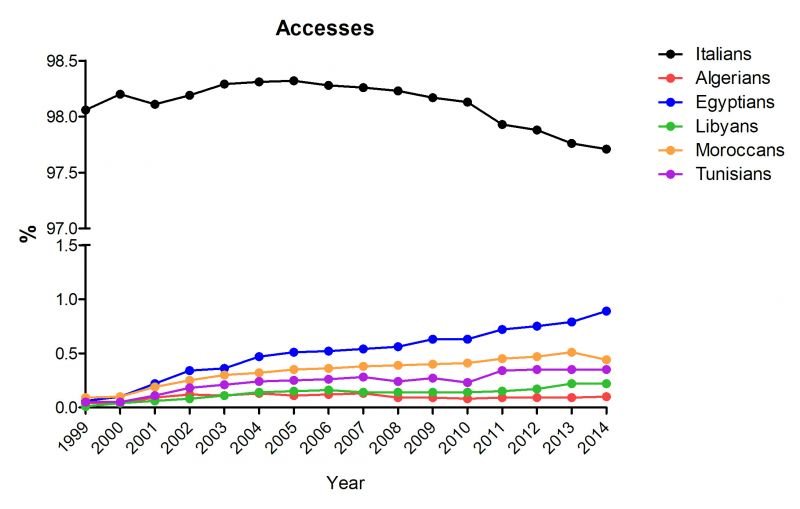

Figure 1

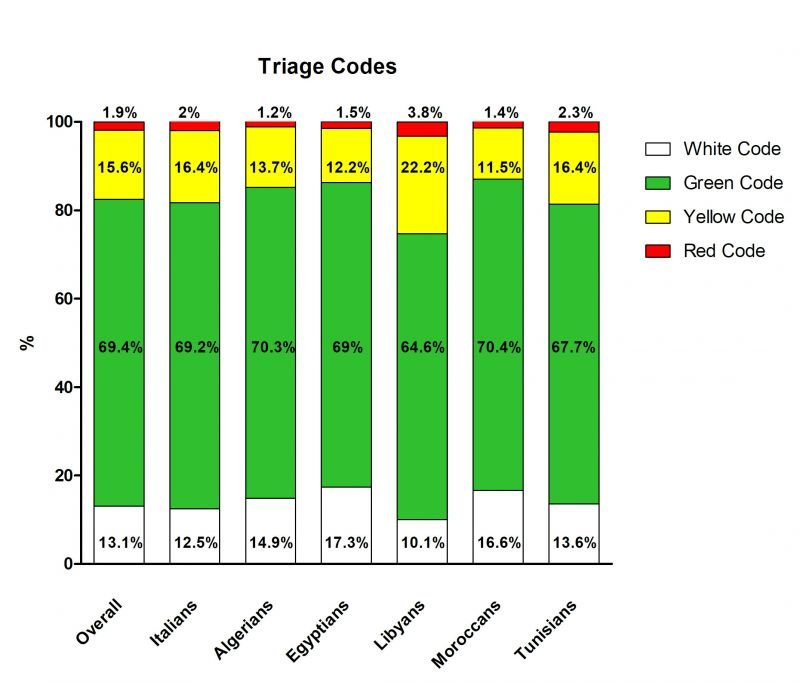

During the period 1999-2014, the overall prevalence of TRIAGE codes was 13.1% for white codes; 69.4% for green codes; 15.6% of yellow codes; and 1.9% for red code. Codes prevalence for the Italian population was very similar to overall prevalence, while the one of Northern Africans was slightly different. Algerians, Egyptians, and Moroccans presented similar frequencies of triage codes, with a higher prevalence of white codes and a lower prevalence for most urgent conditions (i.e. yellow and red codes) than Italians, while Tunisians had a higher prevalence of red codes than Italians. Libyans showed a peculiar pattern, having lesser white codes prevalence (10.1%) and higher level of yellow and red codes (22.2% and 3.2%, respectively) than the other populations (Fig. 2)

As regards the ICD9-CM diagnoses categories, overall the most frequent was “Injury and Poisoning” (group 17:320-389), that was responsible for the 33.3% of the accesses, followed by “Symptoms, signs, and Ill-defined conditions” (18.9%); “Diseases of the Nervous System and Sense Organs” (9.5%); “Diseases of the Respiratory System” (6.4%), “Diseases of the Circulatory System” (6.3%); “Diseases of the Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue” (4.8%), “Diseases of the Digestive System” (3.8%), “Complications of Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Puerperium” (3.3%), “Diseases of the Genitourinary System” (2.8%) and “Mental Disorders” (2.3%), while the remaining presented very low percentages. Italians percentages are absolutely comparable to totals for each diagnosis group. For “Injury and poisoning” category Algerians had the highest percentage (33.9), which is very close to Italians (33.3%), while the rest of Northern Africans varied from the about 27% of Egyptians and Libyans, whom had the lowest percentages, to the 33.9% of Algerians, which had the highest occurrence of these diagnoses category. About “Symptoms, signs, and Ill-defined conditions” Libyans had the highest occurrence (24.1%), while Algerians had the lowest (17.1%), For the “Diseases of the Nervous System and Sense Organs” category all the Northern Africans had an homogeneous behaviour, with a lower prevalence compared to Italians (9.6%), going from 6.2% of Algerians and Tunisians to 8.1% of Moroccans. About the diagnosis category “Diseases of the Respiratory System” Libyans and Italians were similar, showing the lowest values (6.2% and 6.4%, respectively), while the range of the rest went from 7.9% of Tunisians to 9.0% of Algerians. Evaluating differences in the group of “Diseases of the Circulatory System” we found that Libyans had a very higher percentage (8.6%) respect to other populations, where Italians had 6.4% and the rest of Northern Africans varied from 1.8% of Moroccans to 4.5% of Tunisians. Also for “Diseases of Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue” Italians and Libyans presented the lowest values (4.8% and 5.0%), while the others varied from 6.2% of Moroccans and Tunisians to 6.7% of Egyptians. In “Diseases of the Digestive System” there were not important differences. Libyans showed lower values in the category “Complications of Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Puerperium” (2.4%), while Moroccans and Algerians had the highest ones (5.4% and 4.7%, respectively). Absolutely no differences emerged in the category “Diseases of the Genitourinary System” (range 2.6-3.3%). About “Mental Disorders” category Algerians and Tunisians showed a higher value (5.4% and 5.0%, respectively) than the other populations, which varied from 1.7% of Egyptians to 4.3% of Moroccans.

Looking at other diagnosis categories emerged some other differences, even if the percentages in general are very low. It is the case of Egyptians whom distinguished from others for the category “Persons without reported diagnosis encountered during examination and investigation of individuals and populations”, for which had 4.1%, while the rest, Italians included, varied from the 0.4% of Libyans to 1.5% of Tunisians. Libyans showed the lowest values in the group of “Infectious and Parasitic Diseases”, where they had 0.9% while all the rest varied from 1.3 of Tunisians to 1.8% of Algerians and also in the group “Persons encountering health services in circumstances related to reproduction and development” were they had 1.2%, while the remaining varied from 1.5% of Tunisians to 3.2% of Moroccans. Libyans had higher percentages in: “Neoplasms” with the 2.0% while the others varied from 0.4% of Algerians to 1.0% of Italians, “Endocrine, Nutritional and Metabolic diseases and Immunity Disorders” (1.2%), while the rest went from 0.5 of Moroccans and 0.7% of Algerians and also in “Diseases of the Blood and Blood-forming Organs” (Libyans 1.1%, where the rest varied from 0.3% of Moroccans and 0.6% of Italians and Tunisians). For all the others diagnosis categories all the populations were absolutely comparable, having not significant differences in percentages (Data not shown).

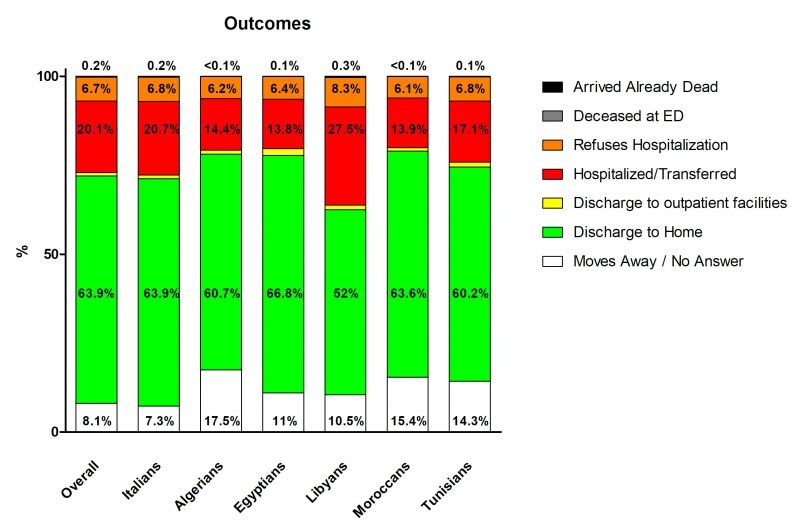

Outcomes at the ED were grouped in seven categories: “Doesn’t answer or left” (8.1%); “Discharged to home (63.9%); “Discharged to ambulatory care” (1%); “Reject the hospitalization” (6.7%); “Hospitalized or transferred to other structure” (20.1%); “Died in ER” (0.2%); “Dead on arrival” (0.1%). The percentages of the outcomes of the Italian citizens were similar to the overall prevalence, while Northern Africans showed some differences. In particular, all Northern Africans showed higher values for “Doesn’t answer or left”, ranging from the about 10% of Libyans and Egyptians to the 17.5% of Tunisians. Libyans showed the lowest prevalence of “Discharged at home” (52%) and the highest prevalence of “Reject hospitalization” (8.3%) while the other population did not differ greatly from the overall prevalence (60.2%-66.8% and 6.1%-6.8%, respectively). All North Africa population had lower prevalence of “Hospitalized or transferred to other structure” (from 13.8% of Egyptian to 17.1% of Tunisians), with the exception of Libyans that again presented the highest prevalence among all groups (27.5%). The categories “Died at ER” and “Dead on arrival” there were not great differences among the populations (0-0.3% and 0-0.1%, respectively). (Fig. 3)

Discussion

Furthermore, socio-economic vulnerability that often exacerbates the potential of integration and therefore the possibility to communicate correctly with the community-based services have a noteworthy effect on access to healthcare services [7]. These obstacles likely contribute to an improper use of emergency services by immigrants, which goes hand in hand with seldom-used preventive care and primary care (e.g. family doctors) services. Policies and practices aimed to strengthening the performance of primary care for immigrants and refugees, fall under a broad range of migrant-sensitive healthcare policies. Primary care is probably the most appropriate level of action for immigrant population. The possibility to access this level of care by the foreign population in the host country is currently quite difficult for immigrants and refugees in particular [8]. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the higher frequencies detected concern specifically the complications during pregnancy, childbirth, puerperium and respiratory illnesses, most of which are avoidable if treated at a community-based level. It is also quite evident that the geographical area of origin represents the variable that most characterizes the differences found between Italians and foreigners from North Africa, in particular with regard to the Libyan population, for whom we believe it will be necessary to pursue a more comprehensive studies that could help to better unify the data concerning the trend of migratory flows with those concerning behaviour towards healthcare services use. Literature dealing with the health of migrants has often focused on immediate emergencies arising from migration and immigration [9], structuring policies that have been limited to targeted interventions for specific diseases or conditions, while a more comprehensive approach in terms of policies must be developed. As clearly seen in the reported picture of North African population data in the five hospitals of Rome, there is no clear definition of emergencies requiring intervention on a specific disease and condition, but rather an implementation and strengthening of primary care for the immigrant population. Policies aimed to improving access, quality, organization and efficiency of primary care should be implemented during the arrival phase at the destination country as well as in the following period.

References

- Rathore MM, Ahmad A, Paul A, Wan J, Zhang D. Real-time Medical Emergency Response System: Exploiting IoT and Big Data for Public Health. J Med Syst.2016 Dec;40(12):283.

- Kuo Y-H, Leung JMY, Tsoi KKF, Meng HM, Graham CA. Embracing Big Data for Simulation Modelling of Emergency Department Processes and Activities. IEEE International Congress on Big Data. 2015.

- IDOS Study and Research Centre. Dossier Statistico Immigrazione 2016 – Rapporto UNAR. Rome: IDOS; 2016.

- De Luca G, Ponzo M, Rodríguez Andrés A. Health care utilization by immigrants in Italy. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2013; 13:1–31.

- Kassar H, Marzouk D, Anwar WA, Lakhoua C, Hemminki K, Khyatti M. Emigration flows from North Africa to Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2014; 24 (1): 2-5.

- Moullan Y, Jusot F. Why is the healthy immigrant effect’ different between European countries?. Eur J Public Health. 2014; 24 (1):80-86.

- UN Habitat/World Health Organisation (WHO). Hidden Cities: Unmasking and Overcoming Health Inequities in Urban Settings. Kobe Centre, Japan. Available online: http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/publications/hidden_cities2010/en/(accessed on 7 September 2016).

- UN Habitat/World Health Organisation (WHO). Hidden Cities: Unmasking and Overcoming Health Inequities in Urban Settings. Kobe Centre, Japan. Available online: http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/publications/hidden_cities2010/en/(accessed on 7 September 2016).

- Priebe S, Bogic M, Adany R, Bjerre NV, Dauvrin M, Deville W, Dias S, Gaddini A, Greacen T, Kluge U, Ioannidis E, Jensen NK, Puigpinósi Riera R, Soares JJF, Stankunas M, Straßmayr C, Wahlbeck K, Welbel M, McCabe R. Good practice in emergency care: Views from practitioners. Migration and Health in Europe. World Health Organisation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation.