- Niki Amadori

- Original Article

Door-to-needle time in acute ischemic stroke: analysing intra-hospital delays, predictive factors, improving strategies. The experience of baggiovara hospital (MO, Italy)

- 3/2017-Ottobre

- ISSN 2532-1285

- https://doi.org/10.23832/ITJEM.2017.019

Abstract

- Primary prevention: public information in order to increaseawareness

- Acute phase management, from the activation of the emergency service tothe rehabilitation and early secondaryprevention

- Health care for survivors withdisability

Case Report

- The adoption of an internal protocol as “priority pathway” in the ER

- Neurologist pre-alerting from the territory

- Immediate TC scanning availability

|

Patient-related factors |

Logistic factor |

|

Uncertainty about symptom onset |

– Incorrect triage |

|

Original from [11] |

- Severe stroke (NIHSS >25)

- Age > 80 years

- Patients on anticoagulants

- Recent surgery/trauma

- Patients over the 4.5 hours, showing “mismatch” areas on advanced neuroimaging

- A dedicated “stroke team” (ER physician – neurologist – neuro-radiologist – radiology technician – nurse) pre-alerted by 118 or ER triage. This team must be readily available when the patient enters the ER.

- The use of weighing beds, each of them coming with a chronometer to optimize the treatment performance

- An advanced standardized neuro-imaging protocol

- Early administration of rt-PA in the ER or TC, postponing any other time-wasting procedure (chest x-rays, ECG, etc.)

Results

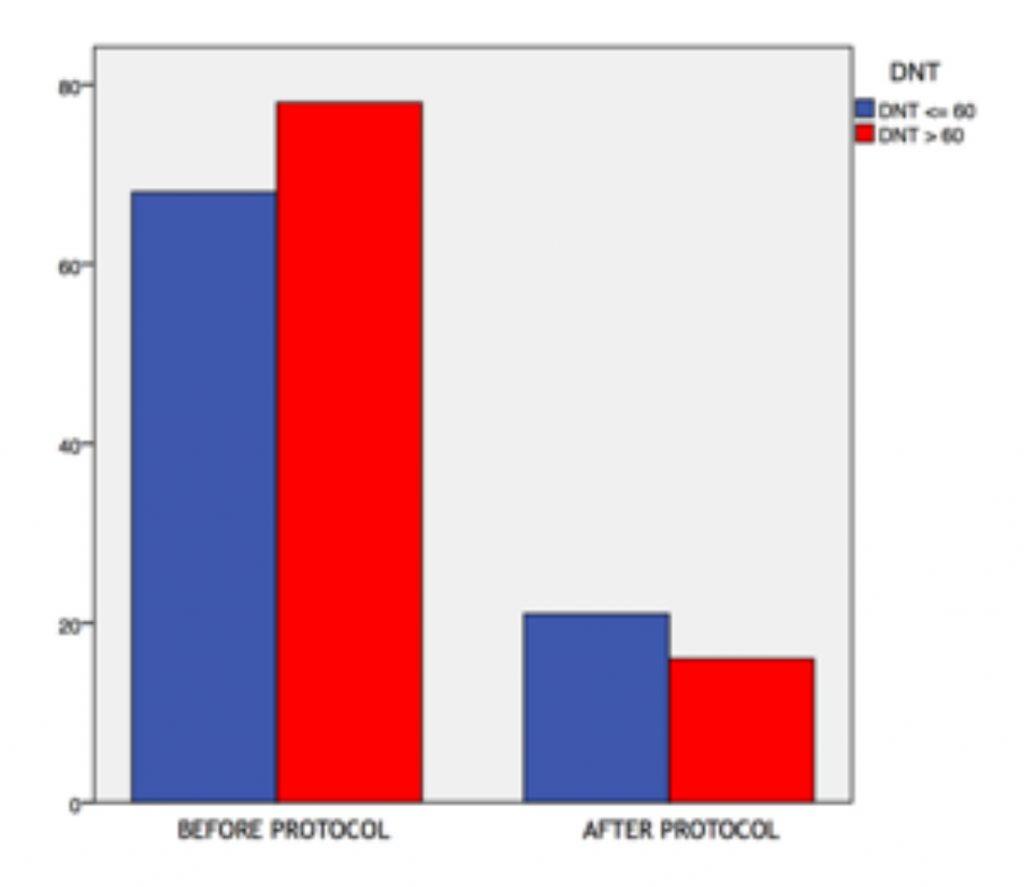

Graph 3

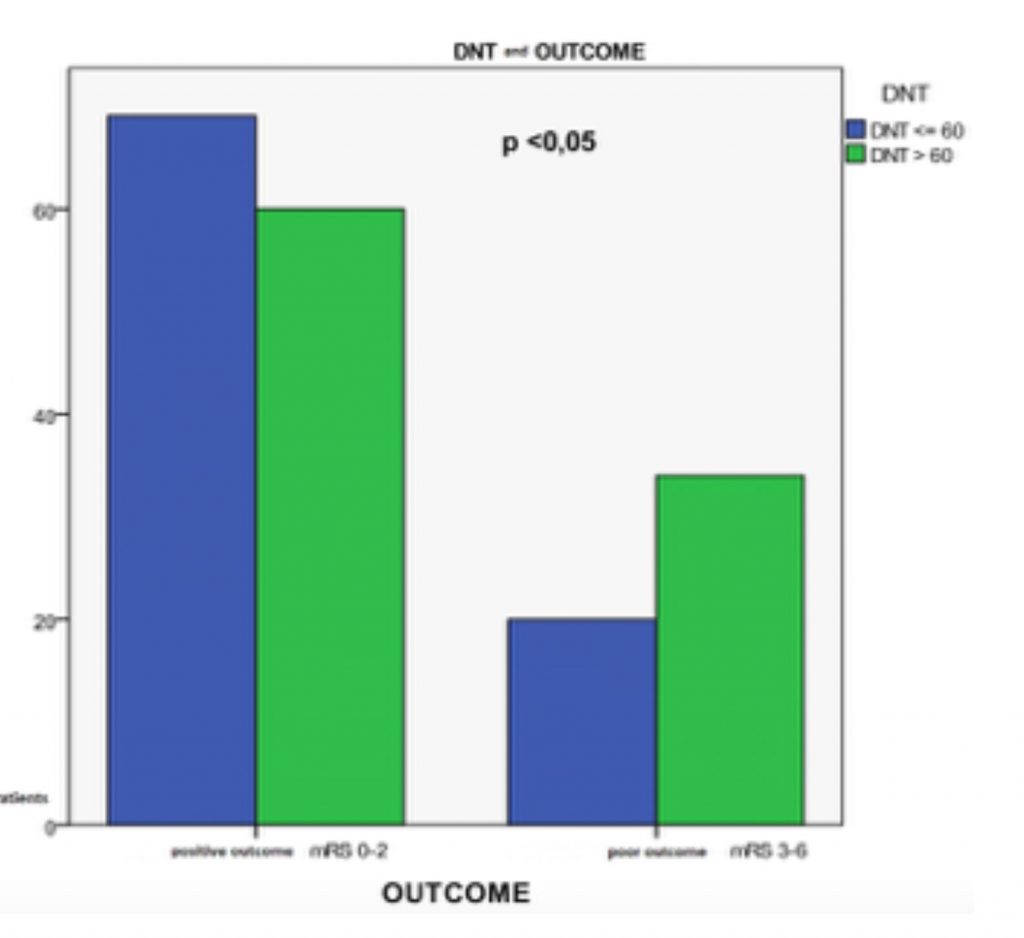

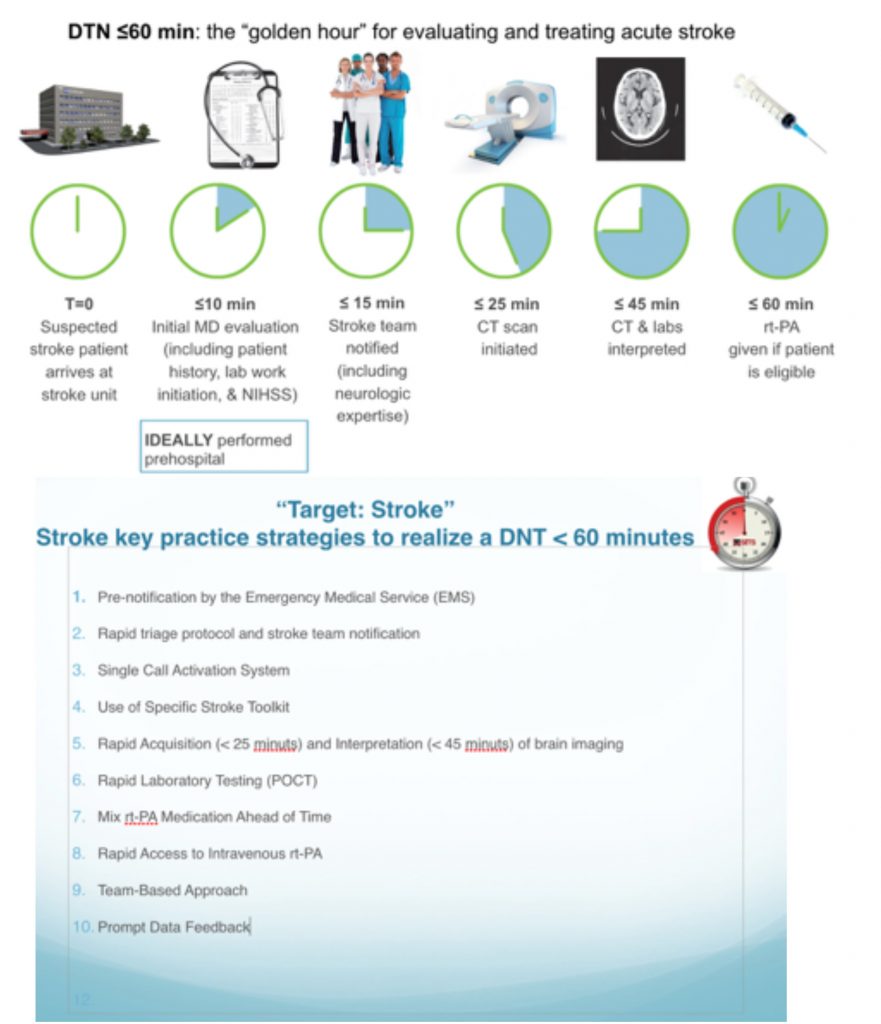

Examining DNT and medium-term outcome, we noted that patients treated before 60 mins showed better modified Rankin Scales, in terms of autonomy and minimal residual disability. This correlation resulted as statistically significant, suggesting the DNT as an independent outcome predictor.

Graph 4

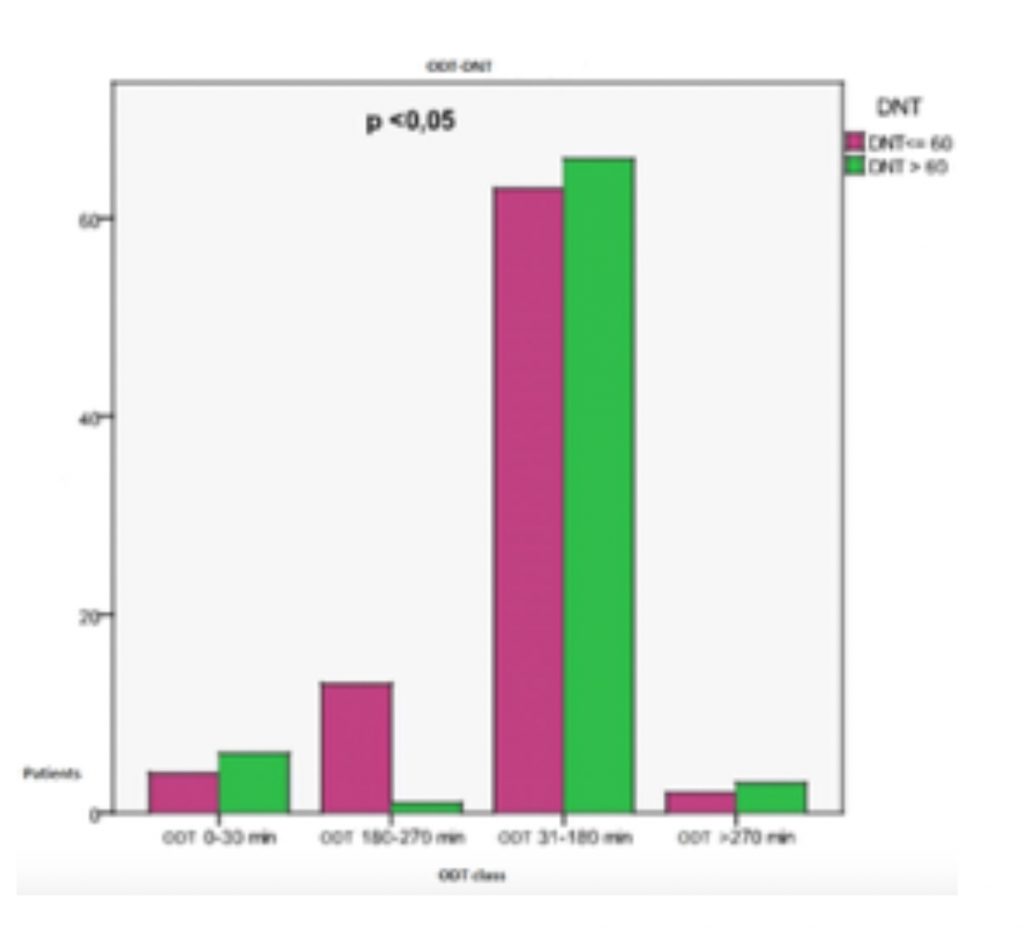

Moreover, the ODT influences the DNT with an inverse correlation; early recognizing of the symptoms, with quick transfer to the hospital, brings the physicians to a less aggressive approach, thus increasing intra-hospital procedure time. This happens for “early” (ODT <3 hours) and “late” (ODT >4.5 hours) patients, while for patients between 3 and 4.5 hours of ODT a quicker behaviour is observed (see Graph 5).

We observed no correlation with the outcome (mRS after 3 months) when comparing ON-label and OFF-label treatments.

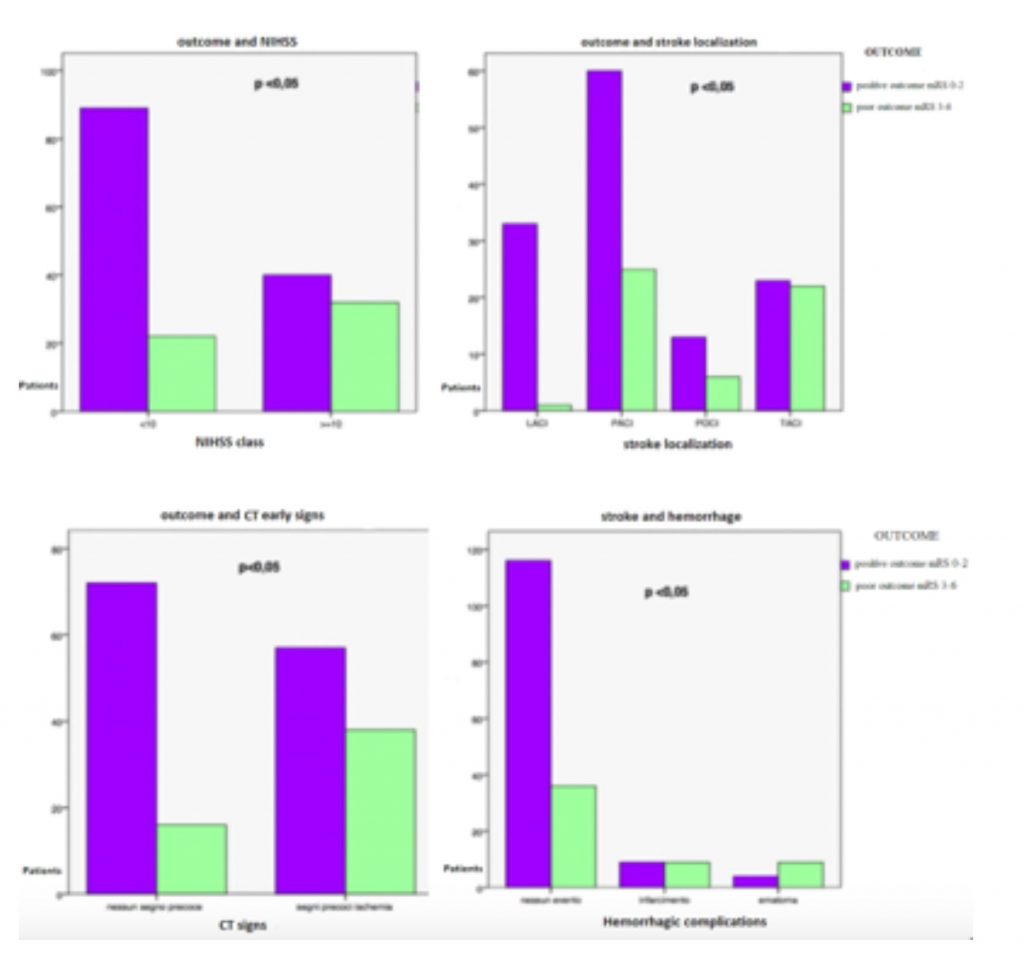

On the contrary, mRS was affected by other variables such as: NIHSS at the time of presentation, site of stroke, presence/absence of early signs in the brain TC, hemorrhagic complications. All of these can be considered independent outcome predictors.

Graph 6

- Outcome was better in patients with an initial NIHSS <10

- Early ischemic signs on the basal brain TC correlate with worse outcomes

- Considering the stroke site (according to the BAMFORD classification), the best outcome was shown after strokes involving small vessels (in particular, lacunar types) or the anterior circulation

- Symptomatic hemorrhagic complications correlate with worse outcomes.

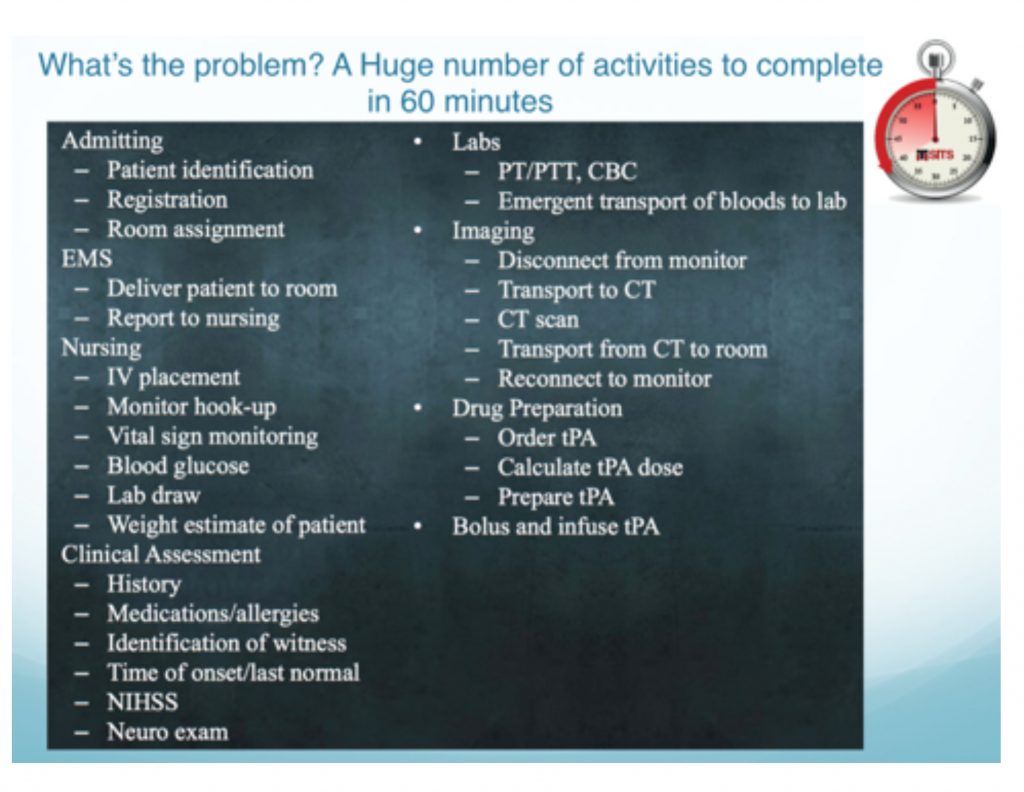

A considerably large amount of key tasks, which have to be performed in the quickest way, among all difficulties of an ordinary ER.

In a well-organized environment, tasks are divided and assigned in order to enable parallel working and reduce the total amount of time needed.

Conclusions

Our data shows that well-designed protocols are effective in improving outcomes for patients with time-dependent pathologies, among which stroke brings a considerable amount of costs in terms of budgets and long-term disability. Teamwork is essential, as well as the constant presence of the right specialist; in our experience, non-vascular neurologists showed to be less incisive in the thrombolytic decision leading to treatment delays.

Further improvements are needed in the recognition and management of posterior circulation strokes (which are not included in the Cincinnati score), even in the pre-hospital setting and during the triage at the ER.

Finally, it is worth noting how the “impression” the physician has from the patient, leads to different degrees of arousal and aggressiveness during the diagnostic-therapeutic path.

Bibliography

- Sander M, Saskia S, Lonneke M.L. de Laub, Renske M and Nyika D. Short Door-to-needleTimes in acute ischemic stroke and prospective identification of its delaying factors Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2015 May-Aug; 5(2):75–83

- Guidetti D, Larrue V, Lees KR, et al. Thrombolysis with Alteplase 3 to 4.5 Hours afterAcute Ischemic Stroke. The New England journal of medicine.2008;359(13):1317–1329.

- Gregg C. Fonarow MD, Eric E. Smith MD, MPH, Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, Mathew J. Reeves PhD, Deepak L. Bhatt MD, Circulation AHA.Timeliness of Tissue Plasminogen Activator Therapy in AcuteIschemicStroke:PatientCharacteristics, HospitalFactors,andOutcomesAssociatedwith Door-to-Needle Times within 60Minutes

- Meretoja A1, Strbian D, Mustanoja S, Tatlisumak T, Lindsberg PJ, Kaste M. Reducingin-hospital delay to 20 minutes in stroke thrombolysis. Neurology 2012 Jul24;79(4):306-13.

- Gregg C. Fonarow, MD1; Xin Zhao, MS2; Eric E. Smith, MD, MPH3; Jeffrey L. Saver, MD4; Mathew J. Reeves, PhD5;Door-to-Needle Times for Tissue Plasmino-gen Activator Administration and Clinical Outcomes in Acute Ischemic Stroke Before and After a Quality Improvement Initiative JAMA. 2014;311(16):1632-1640.