- Andrea Zizzo

- Review

Thoracic Ultrasonography of "FIRE-EATER’S LUNG" in Emergency Department

- 1/2017-Febbraio

- ISSN 2532-1285

Zizzo Andrea(1), Iaccarino Ciro(1), Milocco Mimosa(1), Cipollone Lorena(2), Rosa Antonello(2)

Abstract

Introduction

“Fire-Eater’s Lung” is a rare form of chemical pneumonitis due to an accidental fuel aspiration.

It shows a typical pulmonary pattern, such as multiple unilateral or bilateral alveolar infiltrates, lower lobes involvement, and a clinical severe acute presentation characterized by quick resolution and restitutium.

Case report

A fire-eater young man was diagnosed with “Fire-Eater’s Lung” and therefore was initially treated with oxygen therapy, systemic steroids and antibiotics.

He scarcely improved, then a thoracic bed-side US was made, and highlighted an early cardiopulmonary involvement, which showed the need to start CPAP to achieve immediate improvements.

After few days the patient was able to be weaned from NIV, and early transferred from ED to medical department.

Discussion

This case showed a very typical characteristics about history, physical examination, laboratory tests and radiological patterns.

Thoracic US performed in ED showed a critical role in definition of respiratory distress severity, even when clinical examination doesn’t prove enough. It allowed us to choose for the best therapy leading in a faster clinical and anatomo-pathological remission.

Meta-analyses

“Fire-Eater’s Lung” was always followed by clinicians, radiologists and pathologists, for the rare incidence and the peculiarities of lung damage: wide and severe in almost all cases, but rapidly recovering, compared with ARDS.

To this day, 19 case reports and 2 retrospective analyses were published. The interest to the matter is steadily increasing.

Conclusion

Our purpose is to suggest new diagnostic and monitoring strategy in the management of fire-eater’s lung pneumonitis, which allows bedside investigating, easy repeatability and with low biological risk.

Bed-side US of the lung in ED has not only provided a solid contribution and helped to recognize, with good sensitivity, a mild ARDS pattern, but also showed usefulness in therapy monitoring and in prognostic evaluation.

Introduction

The “Fire-Eater’s Lung” is a rare form of chemical pneumonitis due to an accidental hydrocarbon mixture aspiration, used as fuel.

The pneumonitis is very typical and shows multiple unilateral or bilateral alveolar infiltrates, lower lobes involvement, pleural effusion (sometimes massive), pneumatoceles and rarely pneumothorax.

Common presenting symptoms, few hours after aspiration, includes dyspnea, moderate-severe chest pain, cough, high fever, occasionally hemoptysis, elevation of inflammatory markers (quickly to peak) (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

Acute symptoms might be very severe and often life-threatening. However patients usually show a quick remission of the acute phase and a good recovery within the third week, a good prognosis “quod vitam” (mortality 1%) and a variable “ restitutio ad integrum”, from total lung functional resumption (1, 2, 3, 9, 14,15), to various degrees of pulmonary restrictive syndrome (10, 16) or pulmonary fibrosis (8, 17, 18).

Case presentatio

A 24 years old white man was admitted to “ Policlinic Umberto I” Emergency Department, suffering from chest pain, dyspnea, cough, fever and general malaise since the night before, after involuntary aspiration of an undetermined amount of inflammable hydrocarbon fluid, during fire-eating.

On the day before, suffering from the same symptoms he was visited in another ED, and was treated with antibiotics and pain-control medications, and he was discharged from the hospital against medical advice.

In our ED medical staff assessed his vitals (BP 120/70 mmHg, HR 80/minutes, SpO2 96%, RR 25/minutes, CT 37.7° C) and provided to visit him, founding bilateral basal rales with decreased vesicular murmur. An ABG showed mild acute respiratory failure (pO2 61 mmHg, SaO2 96%, P/F 290, pH 7.49, pCO2 35 mmHg), and laboratory tests showed elevated inflammatory markers [WBC 20.260 c/μl e RCP 26,48 mg/dl (v.n. 0-0,5 mg/dl)]; He was taken besides a chest x-ray which showed extensive basal lung infiltration on both sides, patchy medium-basal infiltration on the right lung, mild pleural effusion on both sides and severe bilateral interstitial thickness.

All this considered, the diagnosis was compatible with aspiration pneumonia or “fire eater’s lung”, so he was treated with “Venti-mask” oxygen therapy, systemic steroid, salbutamol, ipratropium and paracetamol for pain. In order to prevent bacterial superinfection he also started antibiotic therapy with piperacillin-tazobactam.

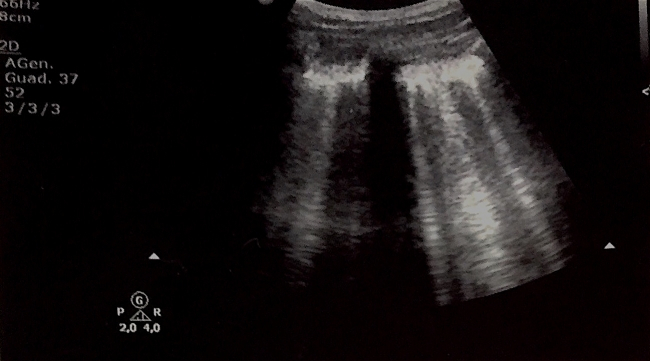

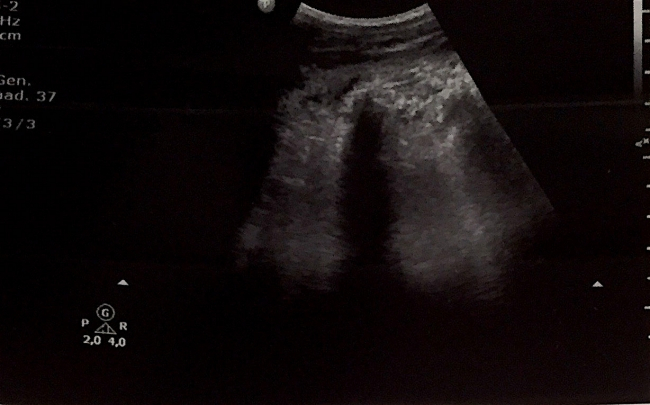

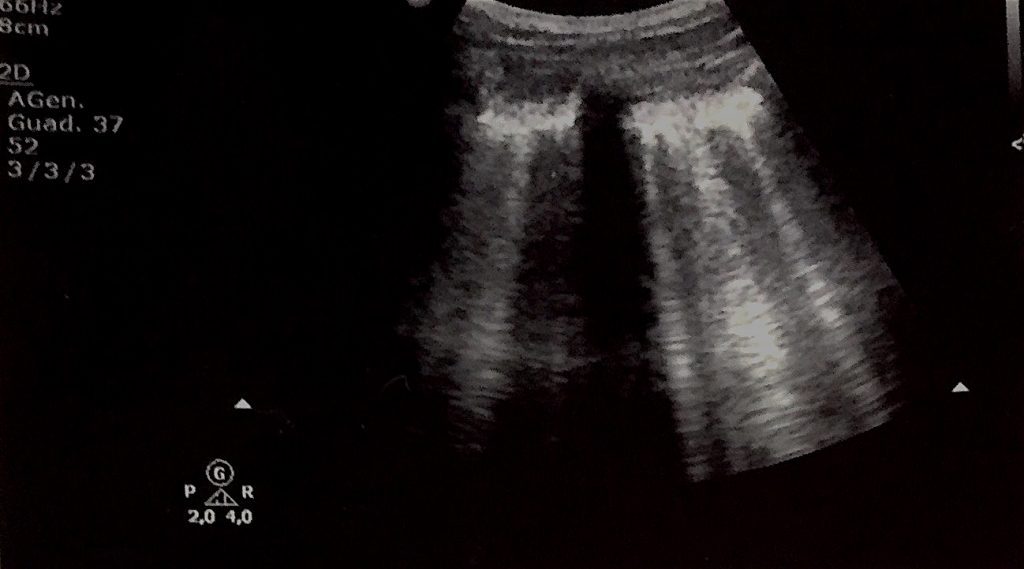

However, after two days therapy, there was ABG worsening (P/F ratio = 188) and no clinical improvement, so it was made a “thoracic bed-side ultrasound” showed more severe cardio-pulmonary conditions: interstitial syndrome (black-white lung) in antero-superior and lateral pulmonary areas with apexes “spared areas”; extensive consolidation of posterior basal right lung and initial consolidation of basal left lung, two subpleural nodular consolidations of medium-lateral posterior left lung; mild bilateral basal pleural effusions. Also pressure overload of the right side of the heart and moderate tricuspidal failure. Maximum diameter of ICV was 2,38 cm, non-responsive to breath.

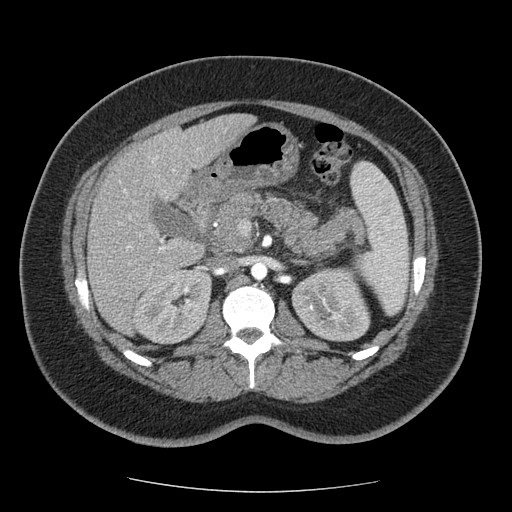

In the same day CT-scan was made, confirming the US results and adding new information of the right medium lobe consisting with atelectasia.

Moreover, on the basis of the new information provided from US and ABG, and considered the serious clinical condition, he started non-invasive ventilation (CPAP with helmet, PEEP 7,5 cmH2O, FiO2 40%) with quickly improvement (pO2 97mmHg, SaO2 99%, P/F ratio 243, pH 7,47, pCO2 42 mmHg RR 22/minute). In doing so, the inflammatory markers rapidly decreased (WBC 15.830 c/μl, RCP 9,67 mg/dl) the day after.

On day four the patient therapy was not necessary anymore, and discontinued continuous cycle of non-invasive ventilation. On day five he was transferred to a medical department.

The acute pneumonitis was totally recovered about fifteen days after. Nevertheless, a restrictive mild ventilator deficit still persisted on spirometry at the end of the second week to aspiration.

Discussion

The Fire-Eater’s Lung is a chemical/toxic pneumonitis that could be an exogenous cause of ARDS, in which a massive inflammatory response consists of parenchymal exudative infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocyte and increase of cytokines (14).

The case showed typical clinical, ABGs, laboratory and radiological findings according to the lack of data, even if not inconsiderable, present in literature.

Despite the lung injury spread and the severity of the clinical condition, according to Berlin 2012 criteria, the patients was been classified as mild ARDS (see Tab. 1). His respiratory function quickly recovered with the appropriate therapy, in contrast to what happens to the other causes of ARDS.

In accordance with literature, a conservative approach, was chosen.

Vitals were continuously monitored, non-invasive ventilation (CPAP, 19) was soon started (10), and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was given to avoid a bacterial superinfection (1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15,16, 17, 20), leading to pulmonary abscess as reported in literature. (21)

Steroid EV therapy was administered (1,2, 9, 15,16,17), despite the lack of data about outcome improvements (20) and their not routinely use (3, 10, 8, 18).

The thoracic bed-side ultrasound made in ED had an important role in the definition of the entity of the respiratory distress and in choosing and monitoring the treatment (23,24,25,26). See Tab. 2.

Tab 1. ARDS Berlin criteria (22)

| Mild ARDS criteria |

|

| (Need objective assessment, eg, echocardiography, to exclude hydrostatic edema if no risk factor present) |

|

Tab 2. US in ARDS

| The thoracic ultrasound findings in ARDS (Copetti, Lichtenstein, Testa,) | |

| Parenchyma |

|

| Pleural |

|

Fig 1. Left Lung US: Anterior axillary-line scan at the level of the 4th intercostal space: IS (ULCs; >3 per scan)

Fig 2. Right Lung Base US: Extensive subpleural consolidation of posterior basal right lung, with static and fluid bronchograms and several hyperechoic spots with posterior enhancement.

Fig 3. Left Lung US: Medium posterior scan showing one of many subpleural nodular consolidations area with hyperechoic spots. Irregular and thickened pleural line, interrupted above the consolidation areas.

Conclusions

Accidental aspiration of liquid combustibles, even if in few dose, may lead to serious lung complications and acute respiratory failure, configuring several patterns, from aspiration pneumonia to ARDS, which could be life-threatening.

Although fire-eaters represent a very small occupational group, the severity of potential risks they take highlight the need of a clinical evolution by specific guidelines.

Through the exposure of our case, we propose the Thoracic Bed-Side US as a new diagnostic and monitoring strategy in Fire-Eater’s Lung. This method provided, in ED context, a solid starting diagnostic contribution, demonstrating a better sensitivity than bed-side x-ray in early recognizing lung impairment compatible with ARDS patterns. The efficiency was comparable to CT-scan images, but achievable at the bedside (23-24-25), with low biological risk because of no radiation use (A TC-chest is equivalent to about 600 chest-RX), and easy repeatability.

Moreover it has proved a good efficiency in monitoring the therapy (25) and in prognostics evaluation.

Tab.3: First, second and third line diagnostic test used in “Fire-Eater’s Lung”

| Chest-X-ray | Chest-CT-Scan | Bronchoscopy and BAL | Spirometry | Chest-US | |

| Our case | + | + | + | + | |

| Ewert | |||||

| Brander | + | + | + | ||

| Burkhardt | + | + | + | ||

| Lampert | + | + | |||

| Kadakal | + | + | |||

| Grossi | + | + | |||

| Vimercati | + | + | |||

| Dell’Omo | + | + | + | ||

| Franzen | + | + | |||

| Pielaszkiewicz | + | + | + | + | |

| Sertogullarindan | + | + | + | +* | |

| Behnke | + | + | +* | ||

| Franquet | + | + | |||

| Olchowy | + | + | + | ||

| Załęska | + | + | + | + | |

| Harding | + | + | |||

| Boots | + | + | + |

*Chest-US in pleural effusion

Bibliography

- Ewert R, Lindemann I, Romberg B, Petri F, Witt C. The accidental aspiration and ingestion of petroleum in a “fire eater”. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1992;117(42):1594–8. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1062481.

- Brander P, Taskinen E, Stenius-Aarniala B. Fire-eater’s lung. Eur Respir J. 1992;5(1):112-4.

- Franzen D, Kohler M. Severe pneumonitis after fire eating. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-006528.

- Baron SE, Haramati LB, Rivera VT. Radiological and clinical findings in acute and chronic exogenous lipoid pneumonia. J Thorac Imaging. 2003;18(4): 217–24

- Franquet T, Gomez-Santos D, Gimenez A, Torrubia S, Monill JM. Fire eater’s pneumonia: radiographic and CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24(3):448–50.

- Grossi E, Crisanti E, Poletti G, Poletti V. Fire-eater’s pneumonitis. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2006;65(1):59–61.

- Dell’ Omo M, Murgia N, Chiodi M, Giovenali P, Cecati A, Gambelunghe A. Acute pneumonia in a fire-eater. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2010 Oct-Dec;23(4):1289-92.

- Olchowy C, Lasecki M, Inglot M, Zaleska-Dorobisz U. Case report of fireeater’s pneumonia in adolescent female patient – evolution of radiologic findings. Pol J Radiol. 2015;80:18–21. 10.12659/PJR.892227.

- Sertogullarindan B, Bora A, Sayır F, Ozbay B. Hydrocarbon Pneumonitis; Clinical and Radiological Variability. J Clin Anal Med 2015;6(1): 117-9 DOI: 10.4328/JCAM.869.

- Behnke et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome after aspiration of lamp oil in a fire-eater: a case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports (2016) 10:193 DOI 10.1186/s13256-016-0960-1.

- Załęska J, Błaszczyk A, Jakubowska L, Szopiński J, Polaczek M, Grudny J, Zych J, Roszkowski-Śliż K. Fire-eater’s lung. Adv Respir Med. 2016; 84(6):337-341. doi: 10.5603/ARM.2016.0044

- Harding FM, Hiddinga BI, Eijsvogel MM, van Baarlen J, Oosterhof-Berktas R. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. Aspiration pneumonitis after fire-eating: fire-eater’s lung. 2010;154(45):A2358.

- Boots RJ, Weedon ZJ.Fire-eater’s lung. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008 May;36(3):449-53.

- Burkhardt O, Merker H-J, Shakibaei M, Lode H. Electron microscopic findings in BAL of a fire-eater after petroleum aspiration. Chest. 2003;124(1):398–400.

- Vimercati L, Lorusso A, Bruno S, Carrus A, Cappello S, Belfiore A, Portincasa P, Palasciano G, Assennato G. Acute pneumonia caused by aspiration of hydrocarbons in a fire-eater. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2006 Apr-Jun;28(2):226-8.

- Pielaszkiewicz-Wydra M, Homola-Piekarska B, Szczesniak E, Ciolek-Zdun M, Fall A. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia – a case report of a fire-eater. Pol J Radiol. 2012;77(4):60–4.

- Lampert S, Schmid A, Wiest G, Hahn EG, Ficker JH. Fire-eater’s lung. Two cases and review of the literature. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131(7):319– 22. doi:10.1055/s-2006-932518.

- Kadakal F, Uysal MA, Gulhan NB, Turan NG, Bayramoglu S, Yilmaz V. Fire-eater’s pneumonia characterized by pneumatocele formation and spontaneous resolution. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2010;16(3):201–3. doi:10.4261/ 1305-3825.DIR.1591-07.1.

- Demoule A, Girou E, Richard JC, Taille S, Brochard L. Benefits and risks of success or failure of noninvasive ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2006 Nov;32(11):1756-65. Epub 2006 Sep 21.

- Steele RW. Corticosteroids and antibiotics for the treatment of fulminant hydrocarbon aspiration. JAMA. 1972;219(11):1434. doi:10.1001/jama.1972. 03190370026006.

- Harlander M, Tercelj M, Sok M, Rott T. Fire-eater’s lung complicated by an infectious abscess requiring surgical treatment. Respirology. 2010 Feb;15(2):379-81.doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01688.

- The ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. JAMA. 2012; 307(23):2526-2533. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5669.

- Copetti R, Soldati G and Copetti P. Chest sonography: a useful tool to differentiate acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema from acute respiratory distress syndromeCardiovascular Ultrasound, 2008 6:16 DOI:10.1186/1476-7120-6-16.

- Lichtenstein DA, Lascols N, Mezière G, Gepner A. Ultrasound diagnosis of alveolar consolidation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2004 Feb;30(2):276-81. Epub 2004 Jan 13.

- Testa A, Soldati G. Ecografia Clinica In Urgenza. Ecografia Toracica: Patologia pleuro-polmonare. CP. 18. ED Verduci.

- Soldati G, Copetti R. Ecografia Toracica. Torino Edizioni Medico-Scientifiche. 2006.

- Gentina T, Tillie-Leblond I, Birolleau S, Saidi F, Saelens T, Boudoux L, Vervloet D, Delaval P, Tonnel AB. Fire-eater’s lung: seventeen cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001 Sep;80(5):291-7

- Franzen D (2), Kohler M, Degrandi C, Kullak-Ublick GA, Ceschi A. Fire eater’s lung: retrospective analysis of 123 cases reported to a National Poison Center. Respiration. 2014;87(2):98-104. doi: 10.1159/000350443. Epub 2013 Jun 21.