- Fabio De Iaco

- Editorial/Insights in Emergency Medicine

Chi stabilisce l’appropriatezza nel dipartimento d’emergenza?

- 1 - Gennaio 2013

- ISSN 2532-1285

Fabio De Iaco

Pronto Soccorso Imperia, A.S.L. 1 “Imperiese”Anche negli Stati Uniti si fanno i conti con la crisi economica e con i rischi che essa comporta per il Sistema Sanitario.

L’ABIM (American Board of Internal Medicine) ha lanciato una campagna, di concerto con una grande associazione di consumatori, che vuole affrontare il problema dei costi della sanità dal punto di vista della possibile razionalizzazione della spesa. La campagna, chiamata “Choosing wisely” (“Scegliere con consapevolezza”) ha l’obiettivo di aumentare la consapevolezza dei medici, i veri dispensatori delle risorse sanitarie (1). Il punto di partenza sta nella constatazione che grandi risorse economiche vengono sprecate in indagini e procedure inutili: un recente articolo del Washington Times calcola che questi sprechi ammontino a 750 miliardi di dollari all’anno (2).

La campagna “Choosing wisely” consiste nell’invitare le Società Scientifiche ad indicare, ciascuna nel proprio ambito, un elenco di cinque procedure potenzialmente superflue, inutili o controindicate. Ad oggi hanno aderito nove grandi Società (allergologi, medici di famiglia, cardiologi, internisti, radiologi, gastroenterologi, oncologi, nefrologi e cardiologi nucleari), ma nel 2013 se ne aggiungeranno altre 25, praticamente tutte le più importanti, con l’ eccezione dell’ACEP (American College of Emergency Physicians).

Le prime nove liste sono già state pubblicate e sono disponibili sul sito della campagna (alcuni esempi: controlli annuali dell’ECG in pazienti asintomatici a basso rischio, test da sforzo in pazienti asintomatici a basso rischio, prescrizioni di FANS a pazienti con ipertensione, scompenso cardiaco o insufficienza renale cronica, ecc.) (3).

La massima parte di queste procedure è rappresentata da indagini di diagnostica per immagini. Pochi mesi fa è apparso sugli Annals of Internal Medicine un articolo che affronta proprio l’argomento dell’eccessivo ricorso alle indagini radiologiche: nell’elenco delle indagini ingiustificate figurano numerose procedure che sono frequentemente utilizzate nei Dipartimenti d’Emergenza (4). Tra le altre:

• imaging in caso di cefalea in pazienti senza fattori di rischio per patologia organica

• imaging per sospetta embolia polmonare in pazienti con bassa probabilità pre-test

• TC addominale per sospetta appendicite acuta

• TC cerebrale per sincope non complicata in pazienti senza anomalie neurologiche

• RX torace preoperatorio in pazienti senza sintomatologia cardio-polmonare.

Non si può non essere d’accordo con questo elenco: sono tutte indicazioni basate sull’evidenza e tutti concordiamo che si tratti di indagini spesso utilizzate in maniera inappropriata. E se consideriamo oltre allo scarso (a volte nullo) vantaggio diagnostico offerto da queste indagini anche il rischio radiologico cui si sottopongono i pazienti (una TC del torace equivale a 500 radiografie del torace) ed il costo delle stesse procedure (mai come in questo periodo sappiamo bene che le nostre risorse non sono infinite) concludiamo in pieno accordo con l’iniziativa dell’ABIM.

Eppure l’ACEP non ha aderito a questa iniziativa: l’argomento è stato oggetto di numerose discussioni (tra cui un’assemblea generale nel corso dell’ultimo Congresso USA) ed è tuttora dibattuto su molti blog statunitensi. I sostenitori della necessità di aderire alla campagna hanno sottolineato la validità scientifica e sociale dell’iniziativa e la necessità per l’ACEP di non restare esclusa da una campagna che ha respiro nazionale e che dà grande visibilità ai partecipanti, mentre i contrari all’adesione hanno portato tra le loro motivazioni (5):

• il timore che l’elenco delle indagini diventi la base per una responsabilità di carattere medico-legale

• il fatto che l’obiettivo dichiarato dell’iniziativa, cioè il risparmio economico, sia in conflitto con l’obiettivo della

“miglior cura possibile” (parliamo di “razionalizzazione” o “razionamento” delle risorse?)

• il timore che le compagnie d’assicurazione possano utilizzare i risultati dell’iniziativa allo scopo di non rimborsare

alcune indagini

• il fatto che, con la pubblicazione della “lista di proscrizione” delle indagini definite inutili, altri specialisti si

pongano come “regolatori” dell’attività dei Medici d’Emergenza Urgenza (e ci dicano cosa dobbiamo o non

dobbiamo fare).

I Medici d’Emergenza Urgenza americani riconoscono che esistono molte procedure eseguite nei Dipartimenti d’Emergenza (non necessariamente singoli test) che sono contrarie all’evidenza ed innalzano i costi in maniera ingiustificata; alcuni esempi riportati dai blog:

• misurazioni del PTT in pazienti in TAO senza altre indicazioni

• infusioni di liquidi in pazienti con colica renale

• cateteri vescicali ingiustificati

• somministrazioni di antiemetici contestuali alla somministrazione di oppiacei

• prescrizioni di antibiotici in assenza di indicazioni (esacerbazioni di asma nel bambino, ascessi cutanei superficiali,

ecc.).

Queste ed altre abitudini ingiustificate, costose e talora pericolose per il paziente si affiancano certamente ad una serie di indagini radiologiche ingiustificate, tra le quali molte TC polmonari ed addominali (6).

L’ACEP tuttavia ha deciso di non partecipare alla campagna dell’ABIM ma in alternativa ha avviato il lavoro di tre commissioni: una che si occupa del rapporto costo/efficacia della cura, una seconda che ha il compito di proporre variazioni al Sistema Sanitario ed una terza che si occupa delle transizioni delle cure (difficile da tradurre in italiano, in pratica si tratta di trovare nuove soluzioni nei rapporti tra i vari attori del Sistema Sanitario al fine di ottimizzare i flussi ed abbattere gli sprechi). Siamo in attesa della pubblicazione dei documenti d’indirizzo prodotti da queste commissioni (7).

La posizione dell’ACEP, in pratica, ci dice che è necessario razionalizzare la spesa, ma che la campagna “Choosing wisely” non è lo strumento adatto. Il presidente ha dichiarato che i membri dell’ACEP avrebbero avuto molte difficoltà a redigere un elenco di cinque esami “inutili”, ribadendo ancora una volta la variabilità e l’incertezza del campo d’azione della Medicina d’Emergenza Urgenza (8).

In altre parole la proposta dell’ACEP, alternativa a quella della campagna promossa dall’ABIM, è la ricerca dell’appropriatezza non tanto nelle singole decisioni diagnostiche o terapeutiche, ma in interi processi in cui il Dipartimento d’Emergenza è solo una tappa.

Al di là dell’interesse culturale per quel che accade negli USA e per le posizioni dell’ACEP, che spesso hanno preceduto di molti anni quelle italiane, la situazione americana ci appare ben distante dalla nostra. Tuttavia dal dibattito emergono alcune considerazioni utili anche per noi: soprattutto emerge, tra le righe, la possibilità di un’appropriatezza nell’ambito dei Dipartimenti d’Emergenza che non può essere individuata semplicemente sulla base delle indicazioni degli specialisti delle singole patologie che affrontiamo. Le caratteristiche – cliniche, organizzative, culturali, legali, sociali – dei Dipartimenti d’Emergenza sono ben differenti da quelle delle altre strutture dell’ospedale, ma in qualche maniera riflettono ancor più fedelmente le caratteristiche della popolazione generale. Il tentativo dell’ACEP sta nell’esaminare non le singole procedure, ma interi “processi di cura”, soprattutto quelli che non si esauriscono nel Dipartimento d’Emergenza ma che continuano sia all’interno che all’esterno dell’ospedale.

L’appropriatezza di questi processi è certamente anche economica, risponde a quei criteri di ottimizzazione delle risorse e di garanzia della qualità delle cure che è l’obiettivo dei più moderni Sistemi Sanitari. I colleghi dell’ACEP si propongono con la funzione di perno centrale in questi processi.

È in questo che anche un dibattito così distante dalla nostra realtà, che contiene elementi che ci sono quasi estranei (il ruolo delle assicurazioni sanitarie, la rimborsabilità di alcune procedure, i risvolti medico-legali) diventa, anche per noi, assolutamente attuale.

Pur con qualche variabilità regionale oggi ogni struttura ospedaliera italiana deve fare i conti con una stretta economica, stretta che sarà sempre più sentita proprio nei Dipartimenti d’Emergenza. È un dato di fatto: la diminuzione generale delle risorse incrementa le richieste verso le strutture dell’urgenza, che a loro volta possono contare su risorse diminuite rispetto al passato. Viviamo lo stesso problema che viene dibattuto in questi giorni anche negli Stati Uniti. Le nostre proposte non potranno essere molto diverse.

Bibliografia

http://www.abimfoundation.org/Initiatives/Choosing-Wisely.aspxhttp://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2012/sep/6/report-health-system-wastes-750b-each-year/http://www.choosingwisely.orgRao VM, Levin DC: The overuse of diagnostic imaging and the Choosing Wisely initiative. Ann Int Med, 157: 574-576, 2012.http://thesgem.com/2012/12/podcast-15-choosing-wisely/http://www.epmonthly.com/features/current-features/choose-wisely-some-tests-are-worse-than-unnecessary/http://www.acepnews.com/index.php?id=495&cHash=071010&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=1945http://www.epmonthly.com/features/current-features/the-wiser-choice-should-acep-join-the-choosing-wisely-campaign-no/Keywords

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, thrombotic events, multiorgan damage, plasmapheresis.

Introduction

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP) is an acute syndrome characterized by the presence of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia.

The first case of TTP was described by Moschowitz in 1924 [1]. Recently, between 1982 and 2001, several authors [2-5] identified in the deficiency of the metalloproteinase ADAMTS13 the primary pathogenic cause. TTP is a rare disease [6-8]. it occurs between 30 and 50 years of age, more frequently in the female sex. In the absence of treatment, mortality exceeds 90%, while it is reduced to 10-20% after adequate plasma plasmapheresis or infusion therapy. However, half the deaths are attributable to complications associated with plasmapheresis and hospitalization (sepsis, haemorrhages, thrombosis, etc.) [9]

Case Report

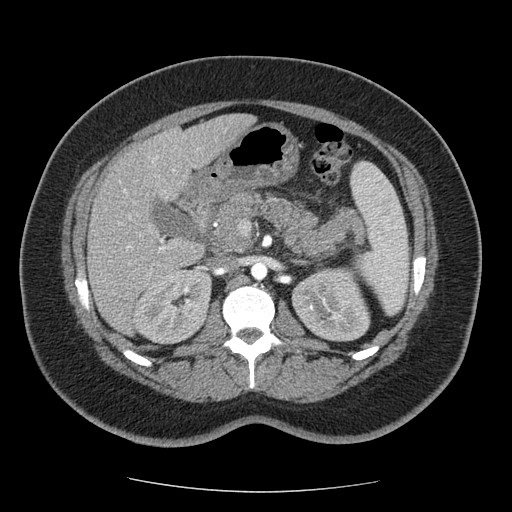

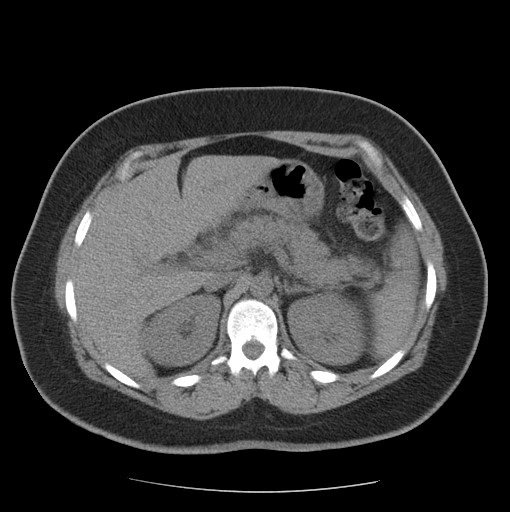

A 36-year-old italian woman came to our observation in the emergency department for abdominal pain, menometrorrhagia and vomiting. The patient had no significant past medical history. She had no significant clinical changes. She was hemodynamically stable.

Figure 1

Discussion

Conclusions

Our case report demonstrates the importance of the rapidity in setting the diagnosis and the treatment of PTT.

Therapy greatly reduces patient mortality. So far, the treatment performed by more physicians is not valid and nonconforming to the guidelines. Platelet transfusions are still administered by many increasing the risk of precipitating further thrombotic events. Their use is contra-indicated in TTP, unless there is life-threatening haemorrhage.

The symptomatology is often nonspecific and the diagnosis is posed with the presence of both microangiopathic hemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Multi-organ involvement, with the onset of acute pancreatitis, may be present.

However, symptoms demonstrating a multi-organ pathological involvement may be an expression of iatrogenic damage.

References

- Moschowitz E. Hyaline thrombosis of the terminal arterioles and capillaries: a hitherto undescribed disease. Proc N Y Pathol Soc1924;24:21-4.

- Moake JL, Rudy CK, Troll JH, et al. Unusually large plasma factorVIII:von Willebrand factor multimers in chronic relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1982;307:1432-5.

- Furlan M, Robles R, La¨mmle B. Partial purification and characterizationof a protease from human plasma cleaving von Willebrand factor to fragments produced by in vivo proteolysis.Blood 1996;87:4223-34.

- Tsai HM. Physiologic cleavage of von Willebrand factor by aplasma protease is dependent on its conformation and requires calcium ion. Blood 1996;87:4235-44.

- Levy GG, Nichols WC, Lian EC, et al. Mutations in a member of the ADAMTS gene family cause thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nature 2001;413:488-94.

- Scully M, Yarranton H, Liesner R, et al. (2008) Regional UK TTP registry: correlation with laboratory ADAMTS 13 analysis and clinical features. British Journal of Haematology,142, 819-826.

- Miller DP, Kaye JA, Shea K, et al. Incidence of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiology 2004;15:208-15.

- Schech SD, Brinker A, Shatin D, Burgess M. New-onset and idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: incidence, diagnostic validity, and potential risk factors. Am J Hematol 2006;81:657-63.

- George JN. The thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndromes: evaluation, management, and long-term outcomes experience of the Oklahoma TTP-HUS Registry, 1989-2007. Kidney Int Suppl 2009;112:S52-4

- Tsai HM, Rice L, Sarode R, Chow TW, Moake JL. Antibody inhibitors to von Willebrand factor metalloproteinase and increased binding of von Willebrand factor to platelets in ticlopidine-associated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:794-9.

- Miller RF, Scully M, Cohen H, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura in HIV-infected patients. Int J STD AIDS 2005;16:538-42.

- George JN. Clinical practice. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1927—35.

- Galbusera M, Noris M, Remuzzi G. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura–then and now. Semin in Thromb and Hemost, 2006; 32, 81–89.

- McDonald V, Laffan M, Benjamin S, Bevan D, Machin S, Scully MA. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura precipitated by acute pancreatitis: a report of seven cases from a regional UK TTP registry. Br J Haematol; 2009;144, 430–433.

- Burns ER, Lou Y, Pathak A. Morphologic diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol 2004;75:18-21.

- George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 2000;96:1223-9.

- Szczepiorkowski ZM, Bandarenko N, Kim HC, et al., American Society for Apheresis; Apheresis Applications Committee of the American Society for Apheresis. Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical practice: evidence-based approach from the Apheresis Applications Committee of the American Society for Apheresis. J Clin Apher 2007;22:106-75.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group. N Engl J Med 1991;325:393-7.

- Allford SL, Hunt BJ, Rose P, Machin SJ, Haemostasis and Thrombosis Task Force, British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of the thrombotic microangiopathic haemolytic anaemias. Br J Haematol 2003;120:556-73.

- Scully M, Cohen H, Cavenagh J, et al. Remission in acute refractory and relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura following rituximab is associated with a reduction in IgG antibodies to ADAMTS-13. Br J Haematol 2007;136:451-61.

- Heidel F, Lipka DB, von Auer C, Huber C, Scharrer I, Hess G. Addition of rituximab to standard therapy improves response rate and progression-free survival in relapsed or refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. Thromb Haemost 2007;97:228-33.

- Foley SR, Webert K, Arnold DM, et al., Members of the Canada Apheresis Group (CAG). A Canadian phase II study evaluating the efficacy of rituximab in the management of patients with relapsed/refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Kidney Int Suppl 2009;112:S55-8.

- Moake JL, Rudy CK, Troll JH, et al. Unusually large plasma factor VIII:von Willebrand factor multimers in chronic relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1982;307: 1432-5.