- Milocco M.

- Original Article

A new way of stratifying acute chest pain: the clinical – chemistry score

- 1/2019-Febbraio

- ISSN 2532-1285

- https://doi.org/10.23832/ITJEM.2019.003

Emergency Department, Policlinico Umberto I, “Sapienza” University, Rome

Abstract

In our study, carried out in the Emergency Department of the Policlinico Umberto I in Rome, we tested a new diagnostic score: The Clinical – Chemistry Score (CCS) (2018).

We selected 143 patients with acute chest pain without signs of STEMI, analyzing the data acquired from the first value of high sensitivity cardiac troponin, from the result obtained from the scores that we selected and from the diagnosis and outcome data. We took the HEART score as a reference and comparison to the CCS.

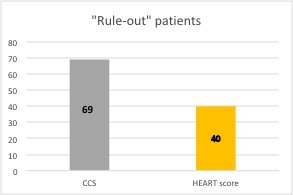

Comparing the two scores, we have demonstrated the validity of the CCS (76% concordance index), the non-inferiority in the “rule-in” and the superiority of the CCS in the “rule-out”.

In our study we have for the first time highlighted the capability of CCS compared to the HEART score to reduce patients in the so-called gray zone, bringing patients to the “extremes” of the risk classification.

Keywords

Clinical – Chemistry Score (CCS) – Acute Chest Pain – Stratification of Risk

Introduction

Acute chest pain management is one of the greatest challenges of the Emergency Departments (ED) worldwide. [1]

Chest pain is one of the most common and complex symptoms for which patients approach to the Emergency Departments; according to some published studies, it causes 5-9% [2] of the total accesses.

Several documents in literature, both at national and international level, have deal over years with the problem of risk stratification in patients that show up to ED with chest pain, proposing a series of implementation strategies. [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

However, this doesn’t lead to data that allow us to have in 100% of cases a correct diagnosis and a short time of observation of the patients “rule-out” for ACS (Acute Coronary Syndrome).

This situation leads to inappropriate hospitalizations, up to 25-50% of patients presenting with chest pain and to inappropriate discharges of 2-8% of patients, with important forensic implications [11] (the erroneous discharge of patients with MI (Myocardial Infarction) accounts for 20% of the forensic expenses against the doctors in the USA Emergency Departments [ 12]). Also give rise to a prolongation of the examination times with a consequent increase in the number of patients under observation and the reduction of the reception capacity of the ED.

For these reasons, the research has focused on new strategies employing both the use of increasingly faster biochemical markers (hs-cTn, High-sensitivity Cardiac Troponin) and the use of diagnostic algorithms and their implementation with scores that define the probability of risk.

The essential concept that drives the medical research to compare the value of troponin with other elements is that troponins do not express only the damage from MI but, in general, they express myocardial damage, even as from different causes. The diagnostic scores rise to support the clinical picture, the EKG and the troponins so to be helpful for a correct classification of the patient.

The Clinical – Chemistry Score is a diagnostic score develop by a Canadian medical team in collaboration with German, Australian and New Zealand doctors and whose primary results were published on 20 August 2018. [13]

The score was studied on 4245 patients in the ED of Hamilton (Canada), Hamburg (Germany), Brisbane (Australia) and Christchurch (New Zealand) and the first results showed a greater sensitivity and specificity in the stratification “rule-in / rule- out”, compared to the use of the only ultrasensitive troponins.

In this study we examine the CCS as a new score to be tested in the ED of Policlinico Umberto I in Rome, make a comparison with the HEART score and test its validity.

The data collected in this study constitute the first experimentation in Italy of this new score.

Case Report

- Both sexes

- Age³18 years

- At least one determination of cardiac troponin

- Informed and written consent

- Chest pain (or angina pain) of suspected cardiac origin and negative EKG for ACS – STE as normal EKG, non-diagnostic / nonspecific EKG or ECG with other ischemic changes (negative T-waves or ST-segment depression).

- Refusal to provide informed consent;

- ST segment elevation to the EKG;

- Pregnancy or breastfeeding;

- Any other clinical condition not judged by the investigator compatible with participation in the TROCAR study.

- HIGH risk patients to CCS (4-5 pt.) and HEART score (7-10 pt.) and ACS +;

- HIGH risk patients to CCS and HEART score and ACS -;

- HIGH risk patients to CCS and LOW / INTERMEDIATE risk to HEART score and ACS +;

- LOW/ INTERMEDIATE risk patients to CCS and HIGH risk to HEART score and ACS +;

- LOW/ INTERMEDIATE risk patients to CCS and HEART score and ACS +;

- LOW/ INTERMEDIATE risk patients risk to CCS and HEART score and ACS -.

- discharged at home, at affiliated and / or ambulatory facilities for further investigations;

- hospitalized with ACS – diagnosis;

- performed coronarography that excluded the diagnosis of ACS.

Results

-

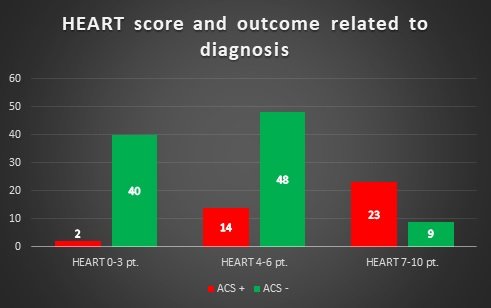

40 patients with LOW risk to HEART score and ACS -;

-

2 patients with LOW risk to HEART score and ACS +;

-

48 patients with INTERMEDIATE to HEART score and ACS -;

-

14 patients with INTERMEDIATE to HEART score and ACS +;

-

23 patients with HIGH risk to HEART score and ACS +;

-

9 patients with HIGH risk to HEART score and ACS -.

Figure 1 – Comparison between HEART score and outcome related to diagnosis

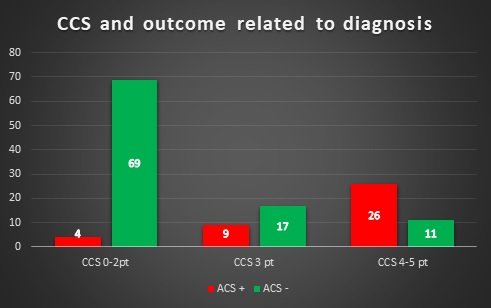

- 69 patients with LOW risk to CCS and ACS -;

- 4 patients with LOW risk to CCS and ACS +;

- 17 patients with INTERMEDIATE to CCS and ACS -;

- 9 patients with INTERMEDIATE to CCS and ACS +;

- 26 patients with HIGH risk to CCS and ACS +;

- 11 patients with HIGH risk to CCS and ACS -.

Figure 1 – Comparison between CCS and outcome related to diagnosis

- 14 patients with a score of 0 to CCS, which 12 discharged and 2 hospitalized (chest pain of unknow cause);

- 29 patients with score of 1 to CCS, which 22 discharged and 7 hospitalized (chest pain of unknow cause);

- 30 patients with a score of 2 to CCS, including 15 discharges, 11 hospitalizations (chest pain of unknow cause) and 4 patients diagnosed with ACS +.

- CCS sensitivity: 0.9 (IC95% 0.82-0.98);

- CCS specificity: 0.71 (IC95% 0.62-0.79);

- Positive predictive Value (PPV): 0.56 (IC95% 0.438-0.682);

- Negative predictive value (NPV): 0.95 (IC95% 0.902-0.998);

- Validity of the test: 0.76.

- Sensitivity: 0.86 (IC95% 0.736-0.984);

- Specificity: 0.86 (IC95% 0.799-0.921);

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV): 0.7 (IC95% 0.562-0.838);

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV: 0.95 (IC95% 0.902-0.998).

- Validity of the test: 0.86.

Discussion

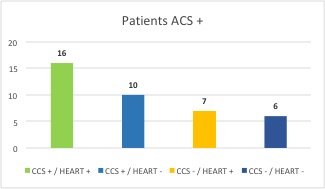

Figure 3. Comparison of HEART score – CCS. Correlation between risk in relation to positive diagnosis for ACS

Conclusions

The capability of Clinical – Chemistry Score to reduce the numbers of patients in the gray area and to bring them to the “extremes” of stratification is the most important data of our study.

Often the gray areas are the weak point of the scores, which make the case of difficult interpretation and, therefore, the reliability of the score in the medical evaluation.

Moreover, it is quite the gray area that limits the direction to make the choice about “rule-out” patients.

In our experience the CCS as compared to HEART has the ability to reduce the number of patients in the gray area by directing them mainly towards “rule-out” and this is an important strength of this new score. Regarding “rule-in” the data of the CCS are similar to the HEART.

The judgment on this score will be validated by expanding the case study, but our preliminary results allow us to see a greater accuracy of this new score.

References

-

Filippo Ottani, Nicola Binetti, Ivo Casagranda, Matteo Cassin, Mario Cavazza, Stefano Grifoni, Tiziano Lenzi, Roberto Lorenzoni, Rodolfo Sbrojavacca, Pietro Tanzi, Giuseppe Vergara – Percorso di valutazione del dolore toracico – Valutazione dei requisiti di base per l’implementazione negli ospedali italiani – G Ital Cardiol 2009; 10 (1): 46-63

-

Tanzi P., Pelliccia F. – La gestione del dolore toracico acuto in Pronto Soccorso. La realtà attuale, le prospettive future, i punti controversi. – G Ital Cardiol 2006; 7 (3): 165-175

-

Aktürk E. Akn L. Taolar M.H. Türkmen S. Kaya H. Comparison of the Predictive Roles of Risk Scores of In-Hospital Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention – Med Princ Pract. 2018;27(5):459-465.

-

Mahler SA, Miller CD, Hollander JE, Nagurney JT, Birkhahn R, Singer AJ, Shapiro NI, Glynn T, Nowak R, Safdar B, Peberdy M, Counselman FL, Chandra A, Kosowsky J, Neuenschwander J, Schrock JW, Plantholt S, Diercks DB, Peacock WF. Identifying patients for early discharge: performance of decision rules among patients with acute chest pain. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168(2): 795–802. [pubmed: 23117012]

-

Fanaroff AC, Rymer JA, Goldstein SA, et al. Does this patient with chest pain have acute coronary syndrome? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA 2015;314:1955-65.

-

Bueno H. The ACCA Clinical Decision Making Toolkit – Second Edition, 2015. ACCA.

-

Kontos MC, Diercks DB, Kirk JD. – Emergency department and office-based evaluation of patients with chest pain. – Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:284-99.

-

Body R, Cook G, Burrows G, Carley S, Lewis PS. – Can emergency physicians ‘rule in’ and ‘rule out’ acute myocardial infarction with clinical judgement? – Emerg Med J 2014;31:872-6.

-

Casagranda I, Cavazza M, Clerico A, et al. – Proposta per l’utilizzo in PS delle troponine cardiache misurate con metodi di ultima generazione in pazienti con sospetta di sindrome coronarica acuta senza sopraslivellamento del tratto – ST. Ligand Assay 2012;17:350-60.

-

Leite L, Baptista R, Leitao J, et al. – Chest pain in the emergency department: risk stratification with Manchester triage system and HEART score. – BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2015;15:48.

-

Guerrino Zuin, Vito Maurizio Parato, Paolo Groff, Michele Massimo Gulizia, Andrea Di Lenarda, Matteo Cassin, Gian Alfonso Cibinel, Maurizio Del Pinto, Giuseppe Di Tano, Federico Nardi, Roberta Rossini, Maria Pia Ruggieri, Enrico Ruggiero, Fortunato Scotto Di Uccio, Serafina Valente – Documento di consenso ANMCO/SIMEU: Gestione intraospedaliera dei pazienti che si presentano con dolore toracico – Giorn Ital di Cardiologia 2016; 17(9); 416-446

-

Mccarthy BD – Missed diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department: results from a multicenter study. – Ann Emerg Med 1993 Mar;22(3):579-82

-

Peter A. Kavsak phd, Johannes T. Neumann MD, Louise Cullen MBBS phd, Martin Than MBBS, Colleen Shortt phd, Jaimi H. Greenslade phd, John W. Pickering phd, Francisco Ojeda phd, Jinhui Ma phd, Natasha Clayton CRA RA, Jonathan Sherbino MD, Stephen A. Hill phd, Matthew mcqueen mbchb phd, Dirk Westermann MD, Nils A. Sörensen MD, William A. Parsonage MBBS DM, Lauren Griffith phd, Shamir R. Mehta MD msc, P.J. Devereaux MD phd, Mark Richards mbchb phd, Richard Troughton mbchb phd, Chris Pemberton phd, Sally Aldous mbchb MD, Stefan Blankenberg MD, Andrew Worster MD msc – Clinical chemistry score versus high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I and T tests alone to identify patients at low or high risk for myocardial infarction or death at presentation to the emergency department – CMAJ 2018 August 20;190:E974-84.

-

Linee guida ESC 2015 per il trattamento delle sindromi coronariche acute nei pazienti senza sopraslivellamento persistente del tratto ST alla presentazione – Eur Heart J 2016;37:267-315

-

Thygesen K, Mair J, Giannitsis E, et al. – How to use high-sensitivity cardiac tro- ponins in acute cardiac care. – Eur Heart J 2012;123:169-72.

-

Body R, Mueller C, Giannitsis E, Christ M, Ordonez-Llanos J, de Filippi CR, Nowak R, Panteghini M, Jernberg T, Plebani M, Verschuren F, French JK, Christenson R, Weiser S, Bendig G, Dilba P, Lindahl B. T.-A. Investigators. – The Use of Very Low Concentrations of High-sensitivity Troponin T to Rule Out Acute Myocardial Infarction Using a Single Blood Test. Acad Emerg Med. 2016; 23(9): 1004–1013.

-

Poldervaart, Langedijk, Backus, Dekker, Six, Doevendans, Hoes, Reitsma – Comparison of the GRACE, HEART and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. – Int J Cardiol. 2017 Jan 15;227:656-661

-

Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. – Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. – Neth Heart J. 2008; 16(6):191–196.

-

Backus BE, Six AJ, Kelder JC, Mast TP, van den Akker F, Mast EG, Monnink SH, van Tooren RM, Doevendans PA.- Chest pain in the emergency room: a multicenter validation of the HEART Score. – Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010; 9(3):164–169.

-

Six AJ, Cullen L, Backus BE, Greenslade J, Parsonage W, Aldous S, Doevendans PA, Than M. – The HEART score for the assessment of patients with chest pain in the emergency department: a multinational validation study. – Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2013; 12(3):121–126.

-

Jaimi H. Greenslade, phd; Louise Cullen, MBBS; Lauren Kalinowski, MBBS; William Parsonage, DM; Suetonia Palmer, phd; Sally Aldous, MD; Mark Richards, phd; Kevin Chu, MBBS; Anthony F. T. Brown, MB CHB; Richard Troughton, phd; Chris Pemberton, phd; Martin Than, MBBS – Examining Renal Impairment as a Risk Factor for Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Prospective Observational Study – Ann Emerg Med. 2013 Jul;62(1):38-46

-

Colleen Shortt, Jinhui Ma, Natasha Clayton, Jonathan Sherbino, Richard Whitlock, Guillaume Pare, Stephen A. Hill, Matthew mcqueen, Shamir R. Mehta, P.J. Devereaux, Andrew Worster, and Peter A. Kavsak – Rule-In and Rule-Out of Myocardial Infarction Using Cardiac Troponin and Glycemic Biomarkers in Patients with Symptoms Suggestive of Acute Coronary Syndrome – Clin Chem. 2017 Jan;63(1):403-414.

-

Rosalinda Madonna, Maria Elena Colella, Raffaele De Caterina – Il controllo glicemico in unità coronarica: valore prognostico e nuove strategie terapeutiche. – G Ital Cardiol 2008; 9 (9): 603-614

-

G. Mathieu – Il Controllo Glicemico Nel Paziente Con Infarto Miocardico Acuto. – Tigullocardio 12-2008 69-73

-

Erhardt L, Herlitz J, Bossaert L, et al. – Task force on the management of chest pain. – Eur Heart J 2002;23:1153-76.

-

Lee TH, Cook EF, Weisberg M, Sargent RK, Wilson C, Goldman L. – Acute chest pain in the emergency room: identification and examination of low-risk patients. – Arch Intern Med 1985;145:65-9.

-

Hollander JE. – The continuing search to identify the very-low-risk chest pain patient. – Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:979-981.